WIP Magazine Issue 11: Interviews

This year, WIP magazine adopted a slightly different approach in format. In addition to our familiar interview and feature sections, as well as our sprawling dossier, the issue included pages dedicated purely to images, and space composed entirely of text. Suffice to say there was something there for everyone. The following interviews are taken from our most recent issue, which quite simply featured a lot of interesting people doing interesting things. Included is the Melbourne-based Collingwood Boxing Club; writer, editor and curator Francesca Gavin; Paris-based skate filmer Romain Batard; Barrington Chang, a Jamaican beekeeper in Liverpool; and Seoul-based multi-hyphenate Suea.

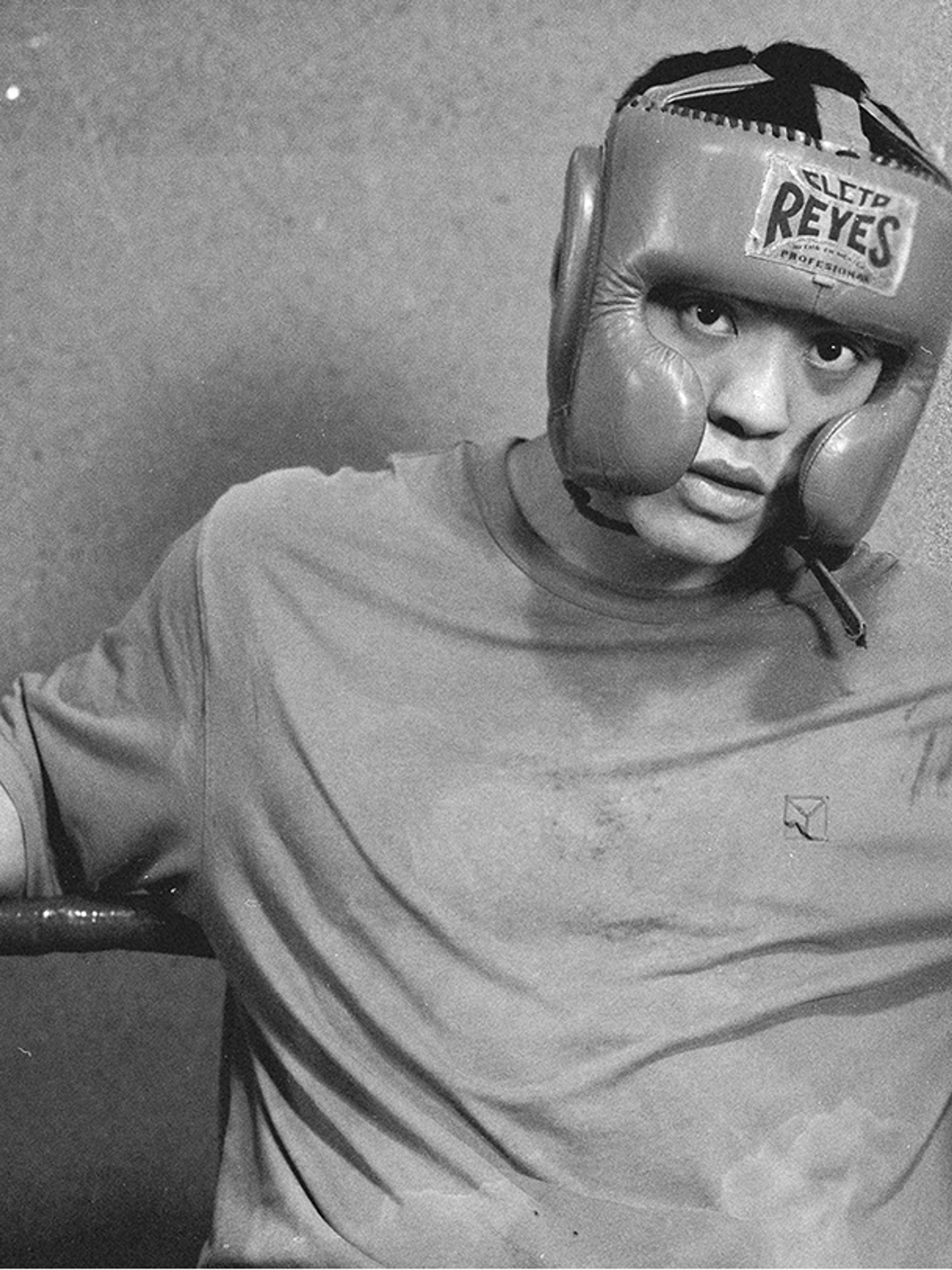

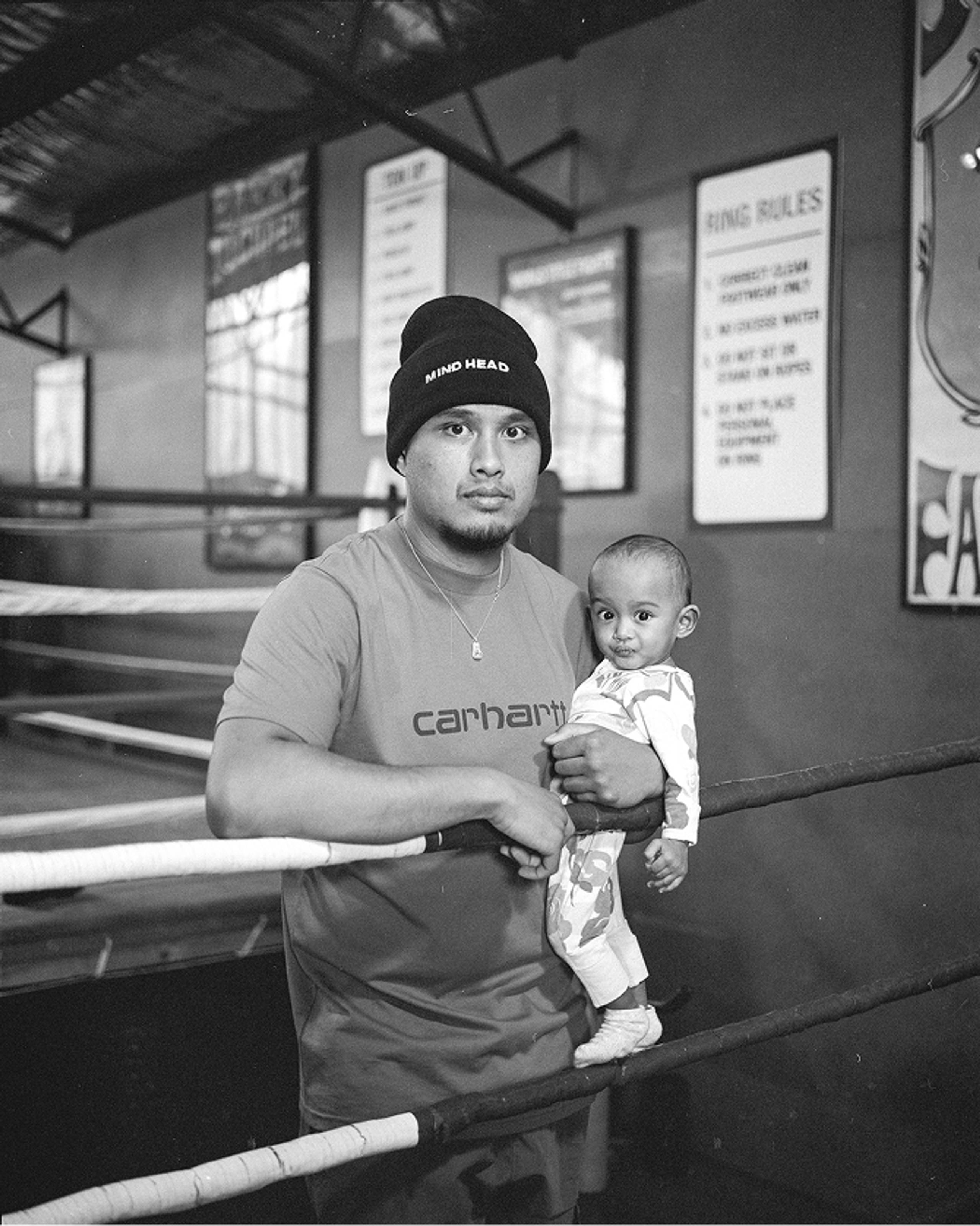

Collingwood Boxing Club

Forged from decay, enter the Melbourne-based boxing club that molds champions and changes lives.

Images: Jye Barclay

Words: Wilfred Brandt

Boxing coach Kel Bryant has a motto: “Hard work brings good luck.” It’s one of those phrases you hear sportspeople use, that sits somewhere between cliche and truism. But when the Australian military veteran found a decrepit building in what was then an undesirable – and fairly dangerous – part of Melbourne, that abstract motto became more like a guiding framework. “The building was lying totally dormant,” Bryant explains, before correcting himself: “It was a shooting gallery for local drug addicts, actually.”

Bryant had been training boxers out of his own backyard when, whilst visiting Sydney for the 2000 Olympics, a colleague told him he had the keys to a building in Collingwood that Bryant should look at. “It was all laying in ruins,” he says. “The roof was hanging off. The floor was caved in. There were two drug addicts shooting up in the lane as I walked up, poor buggers.” Though the building was derelict, residents in the nearby high-rise still had sets of keys. “There was a lot of drug use in the area. They reckon that phone box just around the corner, in front of the town hall, has had more drug-related phone calls go through than anywhere in Australia.”

Bryant opened the building in 2001 as a gym. He started running free boxing programs to help the local community, which back then mostly consisted of Vietnamese and African migrants. Everyone was welcome, he says. “I had the Sacred Heart Mission and the Salvation Army come in. Even the Choir of Hard Knocks started boxing there before they started singing.” Slowly, others began to take notice of his work. Amanda Stone, mayor of City of Yarra – an area that spreads from Melbourne’s east to its northern suburbs – offered to help. Repairs were made and the gym almost doubled in size. “We put table tennis in there and started an adult self-help group. I sank my own money into the building and got it to the point that it was a good, usable gym.”

Bryant’s hard work also impressed another Collingwood local, Mark “Chopper” Read, the notorious Australian criminal and gang member, who would go on to author several best-selling crime novels (and a 2002 children’s book titled, Hooky the Cripple). “Chopper befriended me and would come to the Christmas parties,” Bryant says with a chuckle. “He was a bit of a character. He even offered me $40,000 to run my own gym. It was very funny – but he was basically trying to get in and take it over. I said, ‘What’s this, an offer I can’t fucking refuse?’ He just laughed and said, ‘Ah, you’re alright.’ But he tried.”

In the 25 years since Bryant opened the gym, there are achievements that he obviously takes pride in. He was awarded the prestigious OAM [Medal of the Order of Australia] in 2018 and successfully fought an attempt to have the building bulldozed – it is now heritage listed. But when he’s asked what he’s really proudest of, it isn’t medals or formal recognition, it’s the people who’ve made the boxing club their community. One of them is Marissa Williamson who, at the age of 22, became the first Indigenous woman to represent Australia in boxing at the Paris 2024 Olympics. Just two years prior, she had been without a home. A proud Ngarrindjeri woman, Williamson grew up in the foster care system; through her childhood she was relocated over a dozen times, flitting in and out of homelessness since she was 13. Bryant says that from the moment he first saw her boxing, he knew she had something special: Williamson had raw talent, but more than that, a resilience that would see her keep fighting against any odds: “Character always beats ability in the end,” says Bryant.

Williamson’s story is probably the best known to come out of Collingwood Boxing Club, but there are countless others. Bryant speaks with pride about a young man he helped recruit for the military, who went on to do two tours of Iraq. The man later came back to thank him. (“I didn’t even recognize him,” Bryant says). Or a guy named Andy, who Bryant first discovered washing windows on Hoddle Street. “He’s still part of the club, runs a NDIS [National Disability Insurance Scheme] program and is a qualified social worker. He has really turned himself around. Little things like that are good.”

At age 68, Bryant shows little sign of slowing down, still coaching five or six days a week in the gym. If his long experience coaching has given him a certain perspective, it’s the value of this kind of endurance, of keeping going each day, no matter the odds or setbacks: “In my time at the gym, sometimes I’ve gone head over heels for someone’s ability,” he says “In the early days, I used to miss the kid who was in the corner just punching the bag, time and time again. Now I gravitate to the kid who is there working hard – head down, ass up, getting the job done. It’s the one who is normally unseen that surprises you in the end.”

Francesca Gavin

Rough drafts and the spaces in-between: writer, editor and curator Francesca Gavin explores the recesses of our collective culture.

Words: Holly Connolly

Images: Sirui Ma

Like many contemporary creatives, Francesca Gavin has a multifaceted output. Known as a writer, editor, curator and the host of the NTS show Rough Version, while you could say that Gavin’s primary focus is contemporary art, she is so drawn to the spaces between disciplines that it seems wrong to put her entirely in this realm. There is, however, an obvious unifying theme that runs through Gavin’s work: cross-pollination. This is a word that I borrowed from the mission statement of Epoch, the magazine she co-founded in 2022 with the art director Léonard Vernhet (and which she describes as the best thing she’s done – “It’s fun being able to be both so in depth, and to have such a breadth of reference.”)

“I’m interested in the boundaries between art, music, fashion, pop culture and technology,” Gavin replies when I put ‘cross-pollination’ to her. “I’m an enthusiast; I like sharing things that I find interesting across time, across media, to as broad an audience as possible. My job is to find cultural trends. It’s really about being a giant finger pointing at something cool.” It is a grey, bright February day, and we are sitting at the kitchen table in Gavin’s compact but airy Primrose Hill flat, a dwelling that feels like it could be from the 1999 film Notting Hill; there is even a ladder leading up to a roof terrace, with a panoramic view of the city.

Born in London to a writer mother and actor/musician father, Gavin’s childhood was split between London and America, with the family moving to Los Angeles for a two year stint when she was three, on to Woodstock (a free-spirited town in upstate New York from which the infamous ‘60s festival took it name) until she was ten, then back to London. She credits Woodstock in particular with fostering an enduring love of counterculture. “Growing up in Woodstock made me really fascinated by unusual ways of thinking, and moments where visual art, politics, experimentation and early technology intertwined,” says Gavin. “Most of the exhibitions, and really all the things that I have done, have emerged from this post-psychedelic context, or overlap with technology.”

While it’s not uncommon for people in the creative industries to have had esoteric childhoods and artistic, worldly parents – “We had nothing to rebel against,” as Gavin puts it – it is her sibling dynamic that feels specific, and most formative of Gavin’s work today. One of three, both Gavin’s sisters have carved out similarly successful careers in distinct but adjacent fields: Bianca is the Head of Production for scripted productions at Pulse Films, and Seana is a visual artist. Even from early on, Gavin describes the relationship between the sisters as one of mutual support rather than rivalry, perhaps because their spheres of interest and abilities weren’t quite similar enough for toes to feel stepped on. And with Seana in particular, Gavin took on an early championing role that mirrors her position in spotlighting culture and talent still now. “You could say that my relationship with Seana is my relationship with everyone,” she says. “I've grown up encouraging someone who's creative, and bringing attention to what they do. I’m everyone’s big sister.”

Of everything Gavin does, one of the projects that’s most emblematic of her roving approach might be her NTS show, which has seen her interview artists including Seth Price, Somaya Critchlow, Jenn Nkiru, Mark Leckey and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. A format that’s structured by five songs selected by her interviewees, the conversations on Rough Version center around music and life, rather than strictly artistic output. “Talking about music with people in the art world means that all that training, all that official presentation disappears,” says Gavin. “People just talk about what they connect to. I believe that a good interview is about getting people to take off the mask of professionalism.” (Gavin’s own five tracks would include songs by Nas, Donna Summer and Michael McDonald). Fittingly also for her fluid approach to mediums, in 2022 Gavin brought out a book of the interviews, collected between 2016 - 2021 – “I’m nervous about the longevity of the digital,” she says. “Print it out, otherwise it won’t last.”

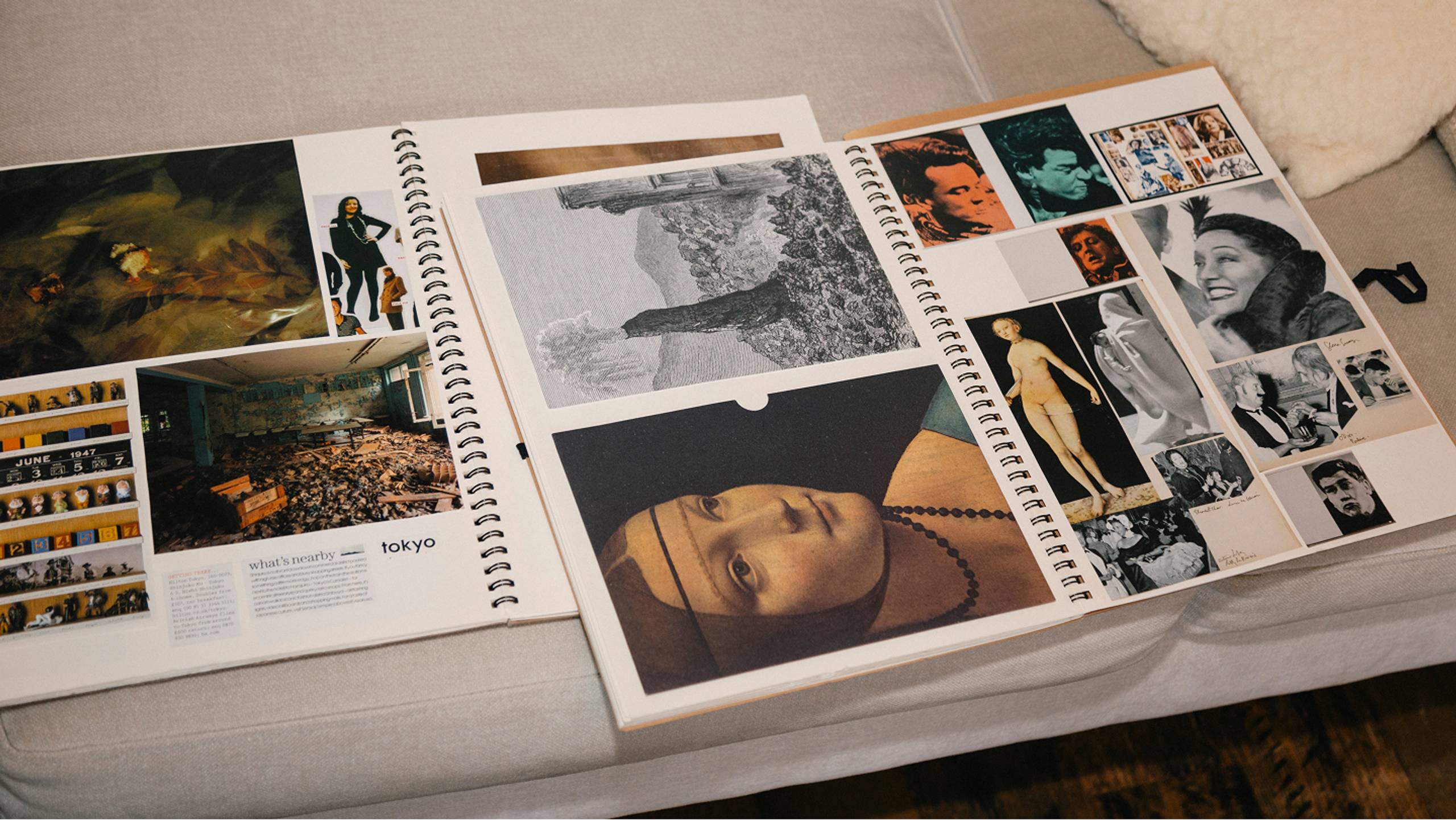

For twenty years Gavin has been making scrapbooks (“hundreds of them”), partly as a means of preserving her huge archive of books and magazines. “It was pragmatic,” she says. “I have so much paper material, so I thought, ‘Well I’ll cut them up and save the best bits.’” She fetches a few down from her shelves for us to leaf through; densely packed books with neat pages laid out like magazine spreads – “I like the [seminal Harper’s Bazaar art director] Alexey Brodovitch style of layout.” These scrapbooks also offer an insight into Gavin’s process: “I get ideas from all of this,” she says. “I really like making combinations that you wouldn't normally see.”

Gavin’s wide approach can also result in a kind of micro-focus, like her 2020 exhibition at Somerset House, “Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi” which brought together hugely varied works from over 40 artists, including her sister Seana, to interrogate the various meanings of mushrooms. “I think once you go deep enough into a subject, you put it to bed. Take mushrooms, I'm finished with mushrooms,” she says. To me this sounds not unlike the arc of some romantic relationships. “Yes, in a way. You fall in love with a subject and get excited by it, and then the relationship has run its course.”

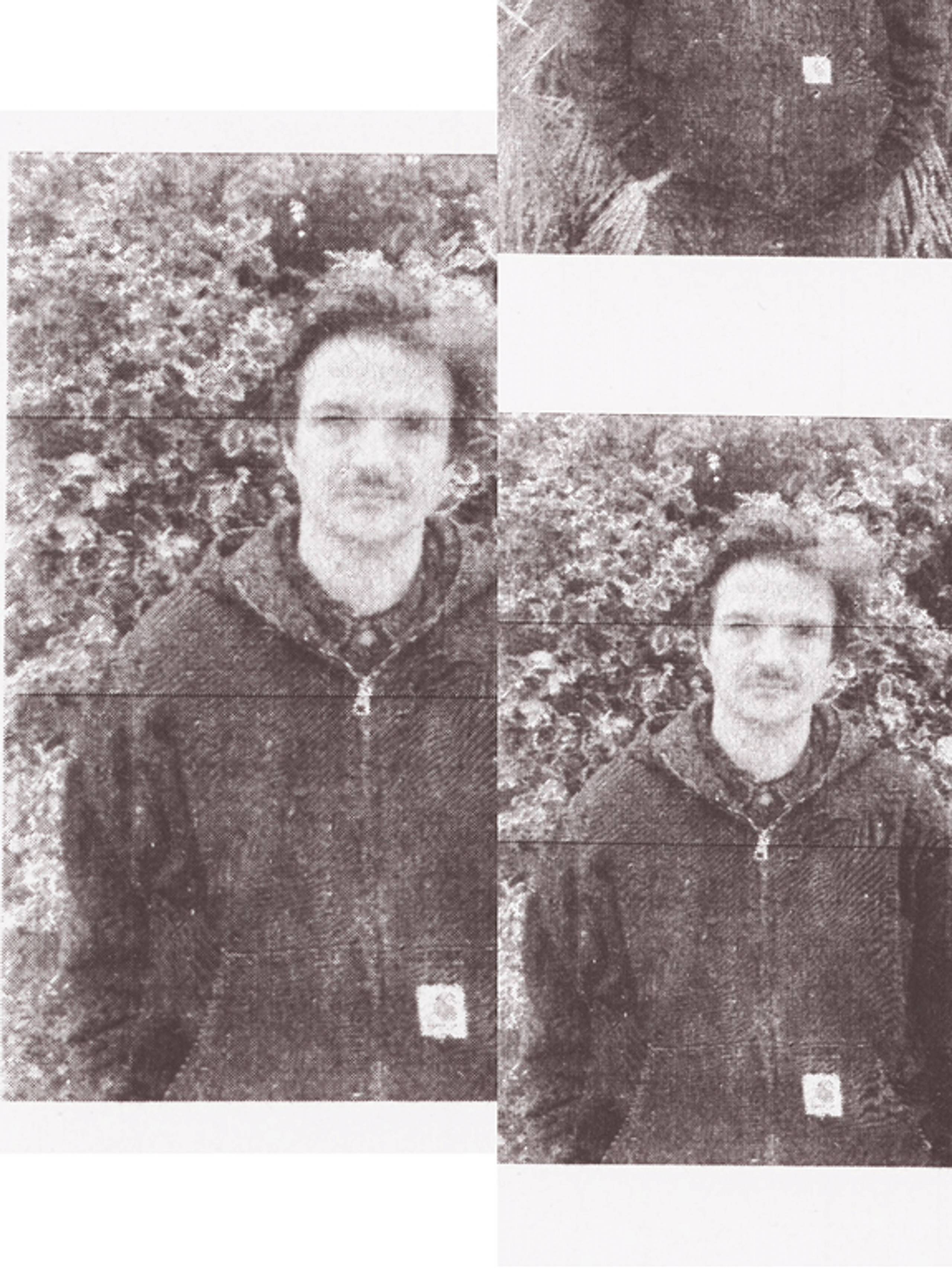

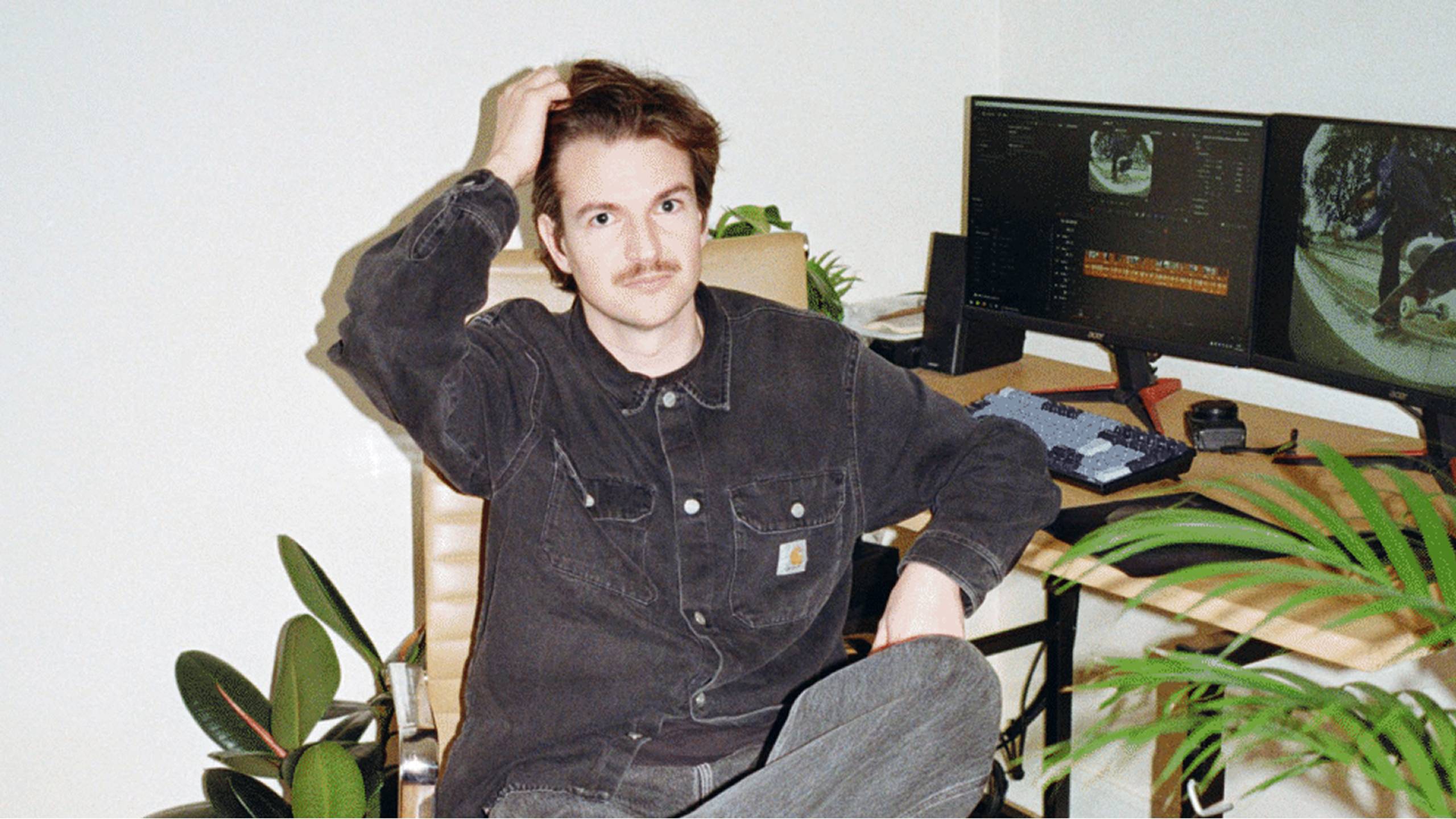

Romain Batard

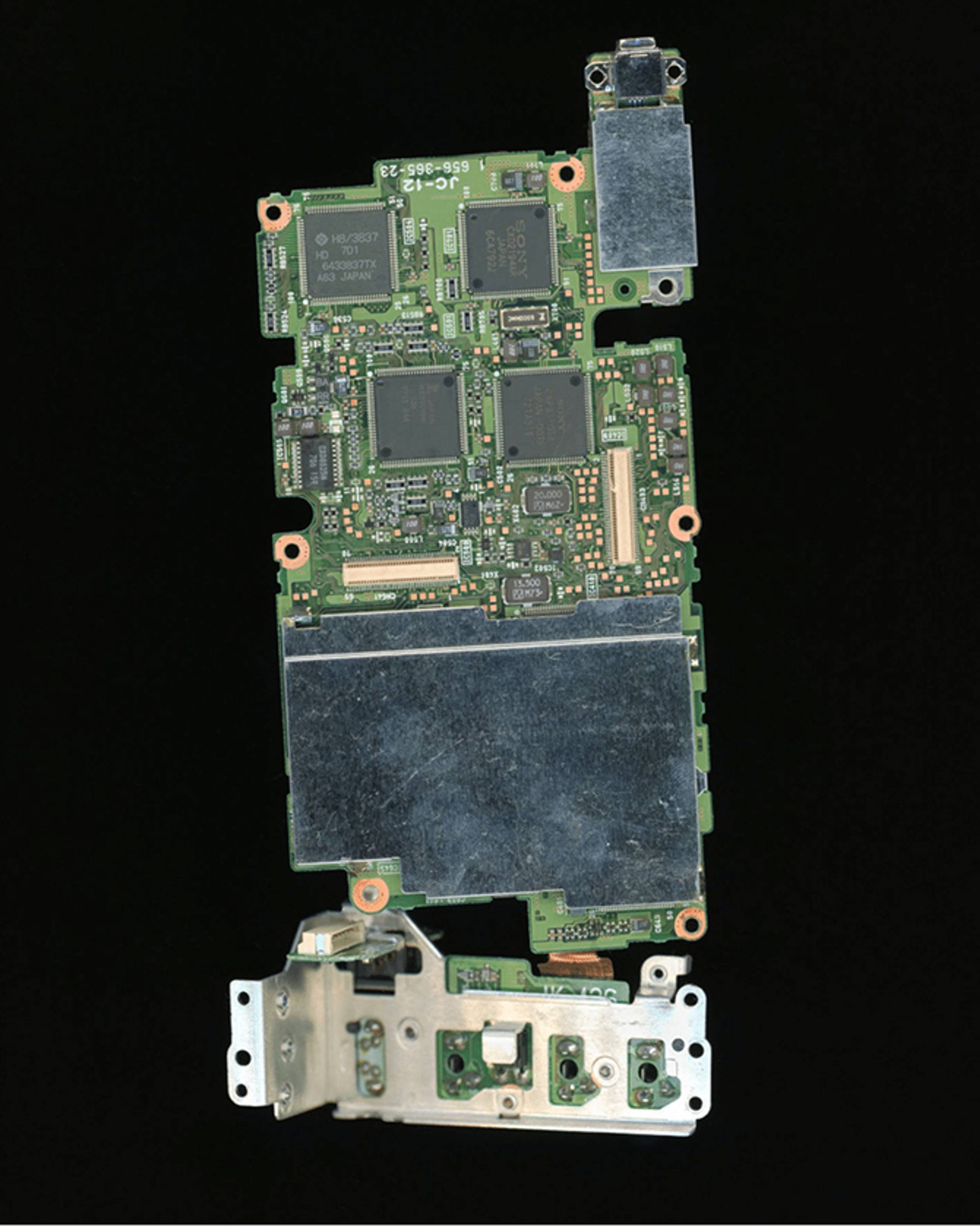

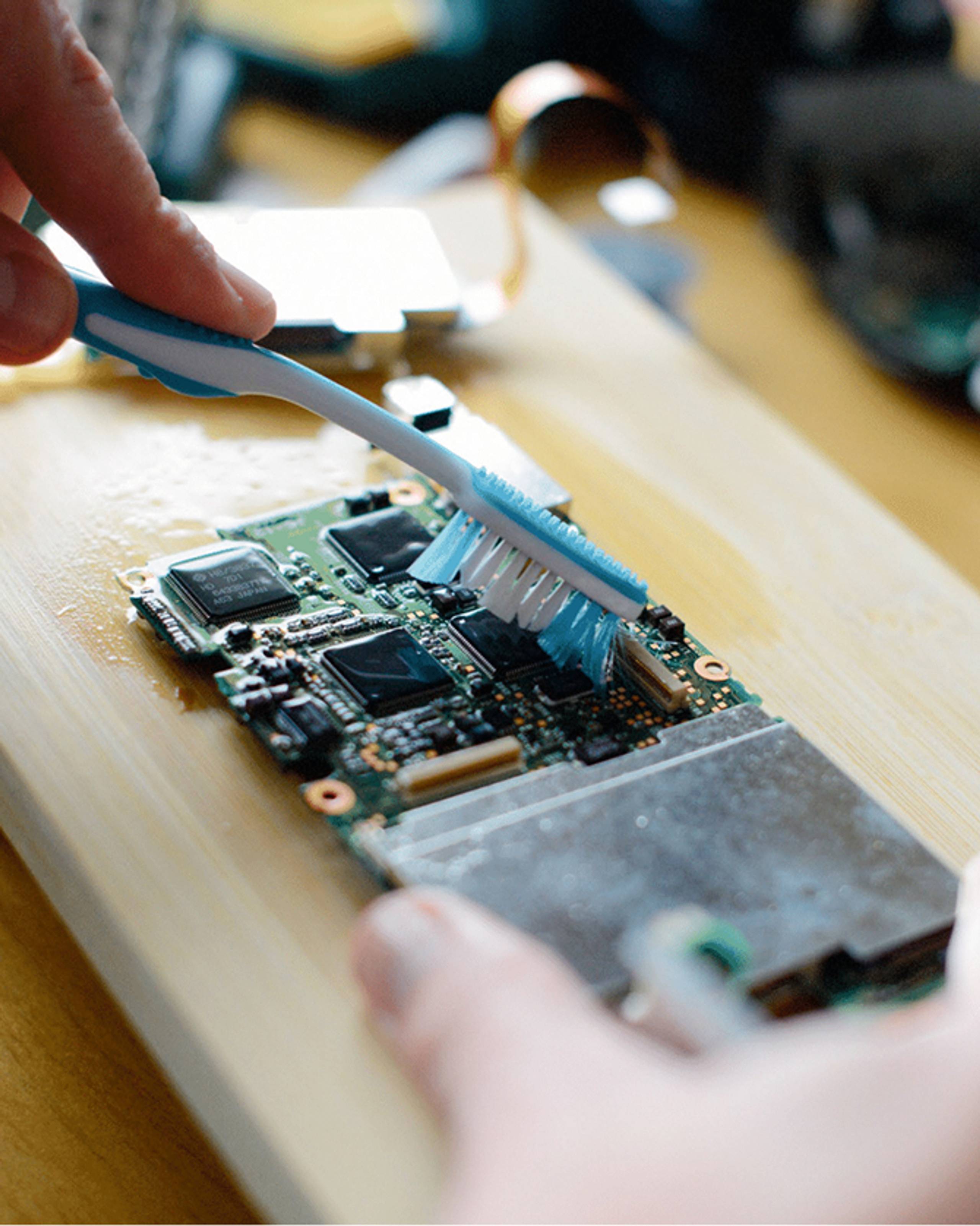

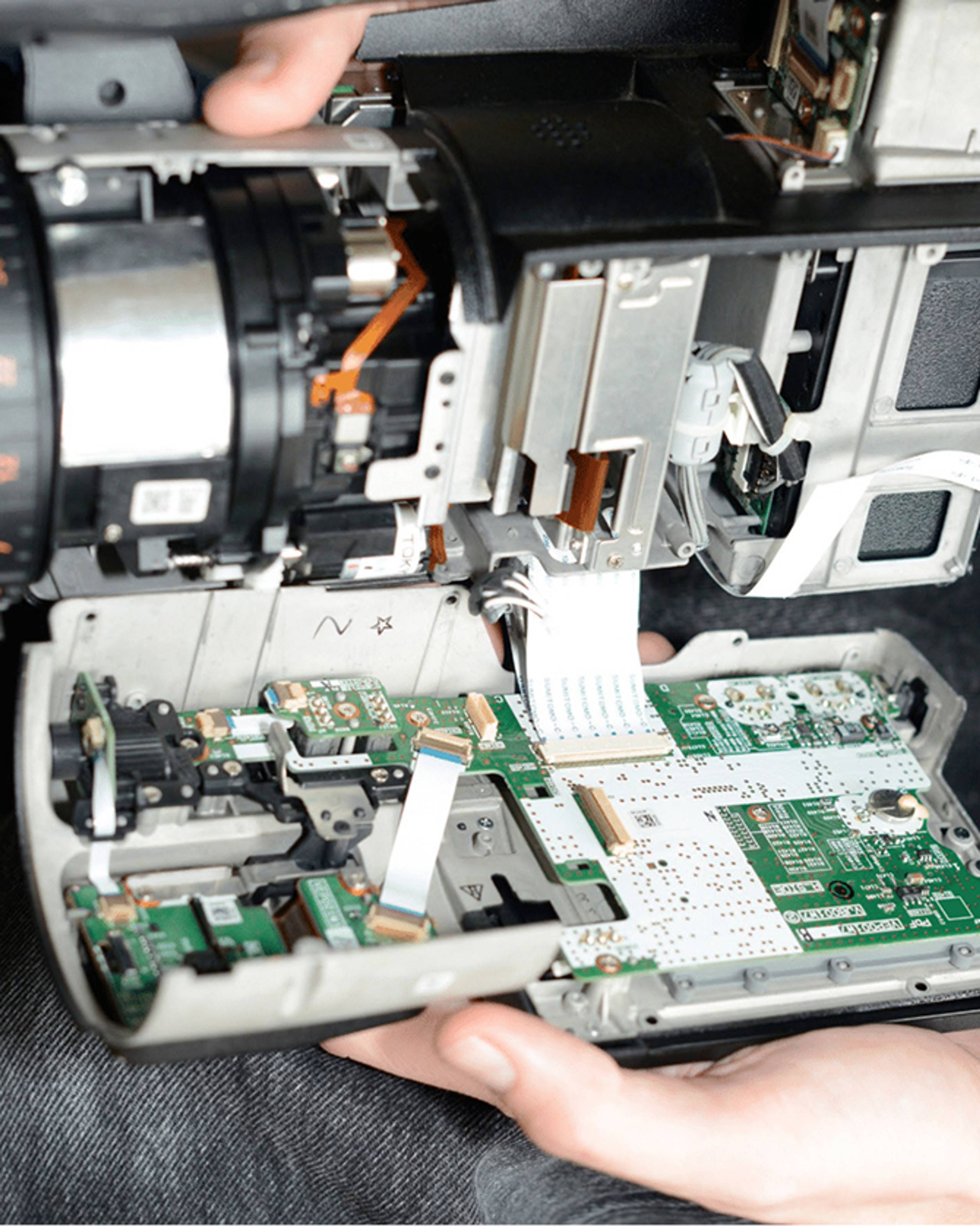

Two skaters best known for their work behind the camera discuss the intricacies of shooting clips, the evolving role of ‘the filmer,’ and Batard’s own Frankenstein camera set-ups.

Interview: Geoffrey Campbell

Images: Yedihael Canat

In a culture that values authenticity above all, what is the role of the person who records the culture? When it comes to skate videos, there is a delicate balance to be struck: capture everything in its rawest, least embellished form, in a way that will appeal to certain purists? Or create something more expressive, more vivid or even poetic? Without certain flourishes, a clip can easily fade into the background, becoming lost among an endless flood of online skate content. But equally, you are working with human beings – usually friends – who may be less enamoured with the idea of repeating a trick, and potentially risking injury in the process, just because the lighting wasn’t quite right.

A skater first and foremost – albeit a “terrible” one – Romain Batard has been filming skate tricks for 20 years. Throughout that time, he has grappled with the challenges his particular role presents, understanding the subtleties and tensions present in any clip. “It’s not something you do independently,” he says. “It's the work of two people. You can't be too selfish about that.” Watching Batard’s footage, his style and presence behind the lens is apparent. Ever technical and precise, his work is also dynamic; characterized by idiosyncrasies or moments of tongue-in-cheek humor. It is evident in his work on Carhartt WIP’s full-length skate film INSIDE OUT, notable for Batard’s use of fish-eye distortion, just as it is in the cinematic cuts in his online video clip “Giddy #08.” In conversation with Geoff Campbell, a renowned filmer in Australia’s skate scene, Batard discusses his DIY camera set-ups, learning from YouTube tutorials, and whether, one day, his role might become obsolete.

Geoff Campbell

How did you first get into filming? Was there a specific moment where you knew that you would be the filmer?

Romain Batard

I was – and still am – terrible at skating, so I realized that if I wanted to keep hanging with my friends, I had to start filming. The first skate magazine I bought came bundled with a video, which also inspired me to film. My parents lent me their old VHS camera and I began filming everyday. I didn’t have a way to plug it into a computer, so I edited directly from the VCR, constantly rewinding and fast-forwarding through tapes. I came from a small town with no other filmer to look up to, so I taught myself everything – mostly through the internet and on forums like Skate Perception. I never saw it as a career in the beginning. It was more of a passion project until I finally landed my first real job in skating 13 years later.

GC

You often change camera setups between different projects. What's the purpose of this?

RB

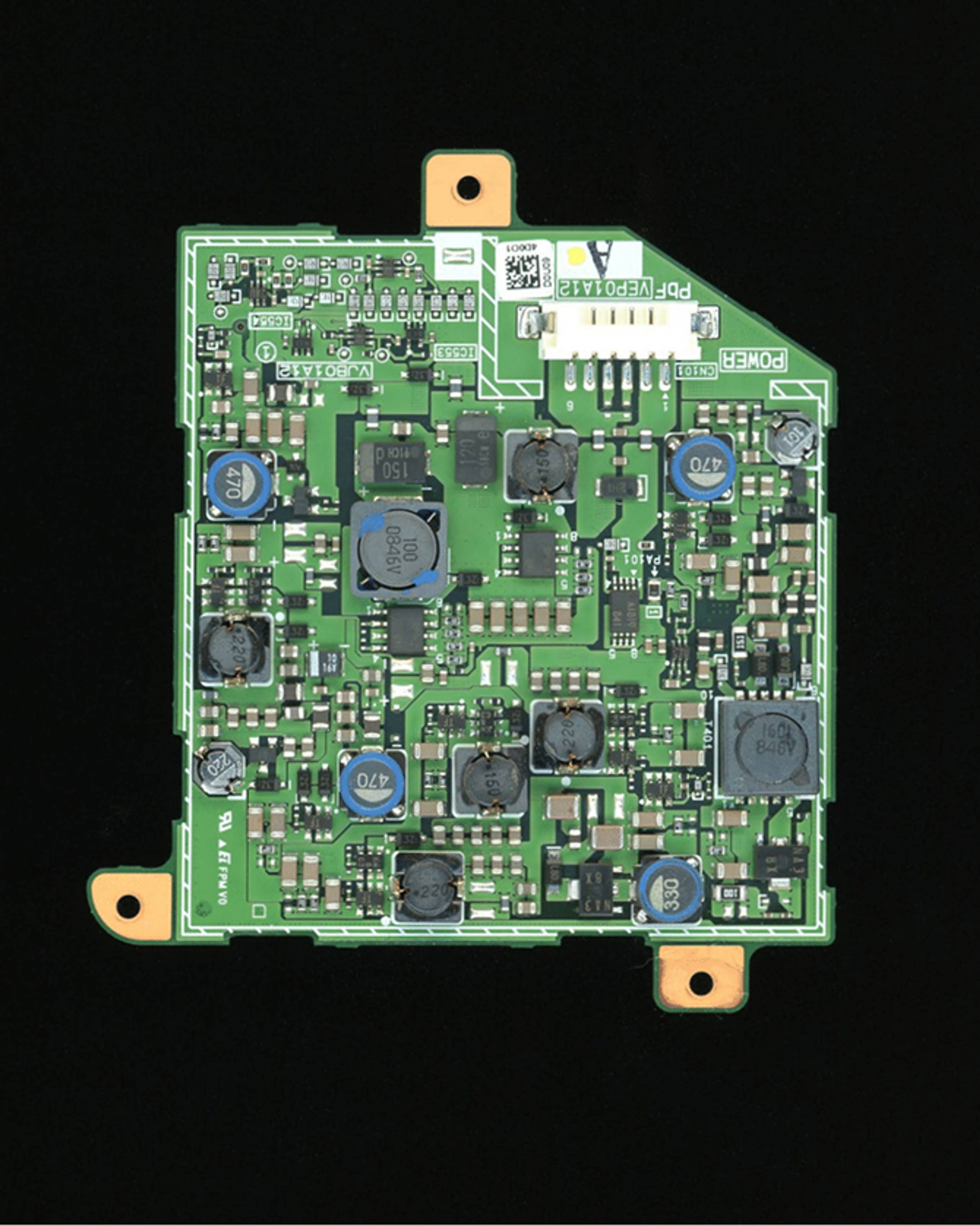

I like to adjust my setup based on the final diffusion. For example, I prefer filming in 4:3 with the MK1 fisheye for social media. The final image has more distortion, which looks better, in my opinion. Beyond that, I like playing with different setups. Trying different cameras and finding something that works for me.

GC

Is changing cameras also a way to stand out and do something different?

RB

I wouldn’t go as far as saying it’s to stand out, because that takes more than just a camera. That involves choosing the right angles, editing, music selection, and graphic design. Some cameras have a distinct vibe that can be mimicked, but at what cost? You can replicate the gritty look of an Hi8 camera in post-production, but it's extra work and is rarely perfect. So why not use the right camera from the get-go? Different cameras can make your subject look good, but skaters expect certain standards.

GC

If it was possible, is there a combination of all the different cameras you use that would create the dream setup?

RB

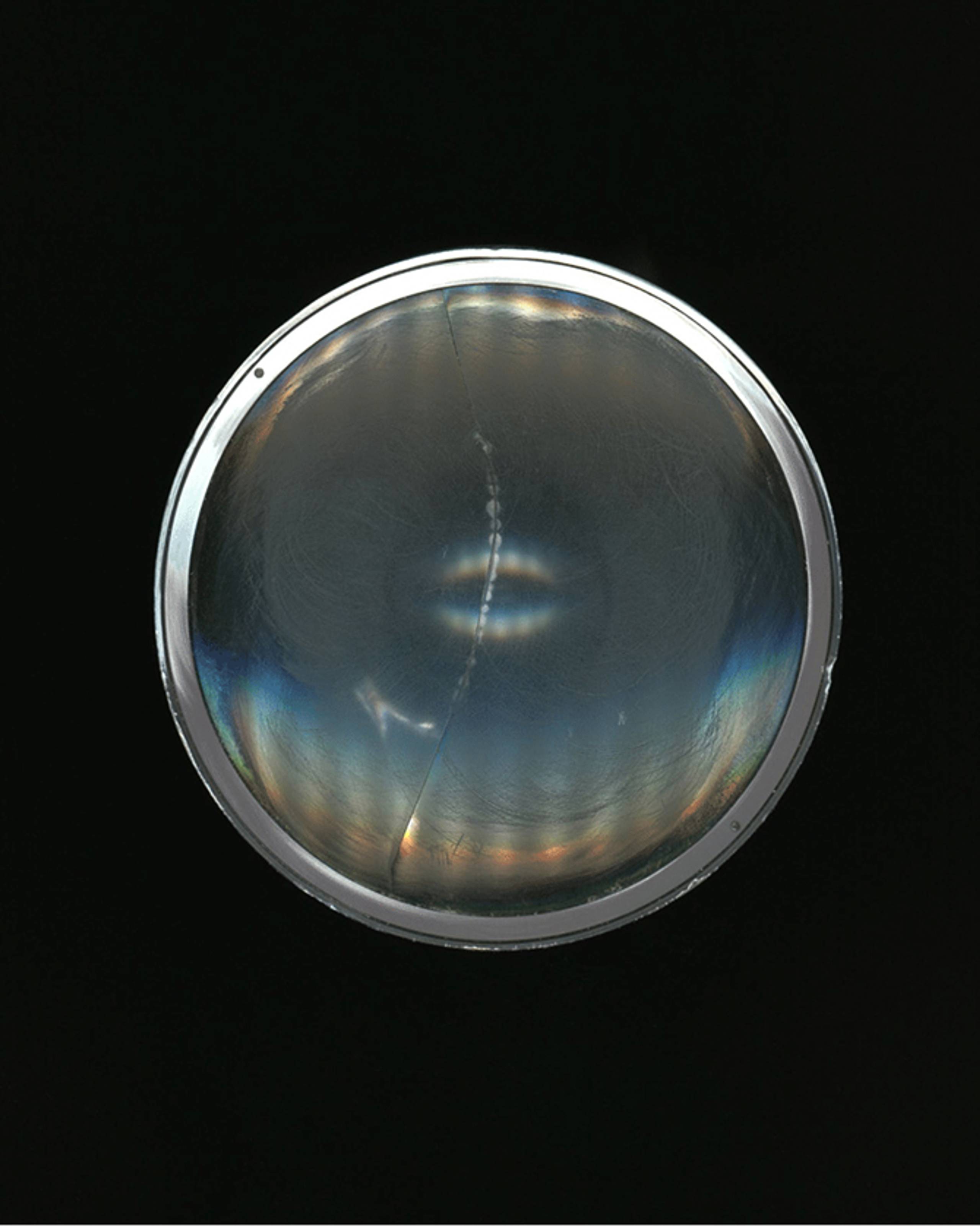

The main thing with skating is the fisheye. The Xtreme fisheye is ideal for this, but it's huge, and made for an old, fragile camera. I wish there was a smaller version of this fisheye that could be adapted to different cameras. I see more FX-6 in the mix these days, so creating a new fisheye for it would make sense, and position that camera as the new reference. The FX-6 camera is solid, but its fisheye options aren’t great for skating. A fisheye that offers more vertical distortion with sharp vignetting would be perfect.

GC

When it comes to filming skate videos, being original and having your own style is important. But do you think there's something truly original that can be done that hasn't already been hinted at before?

RB

I'm sure there’s a lot still left to explore, but skaters can be a tough crowd. We tend to stick to certain standards as much as possible. For example, the main camera used these days is 15 years old. Why is that? I’ve had ideas in the past that didn’t end up happening because the skaters didn’t want to try something different, or were afraid of how it would turn out. It’s a delicate balance, trying to introduce something new without going too far from the norms. But I get where they’re coming from – when someone is jumping for hours, putting their all into a trick, they want it to be filmed in the most flattering way possible. So the safest approach would be to stick to those filming conventions.

GC

How do you feel about asking a skater to do a trick again? Say if you’ve tried to film something in a special way, but they didn’t quite land it. Then when it does land, the filming wasn’t the same for you.

RB

Usually I take the hit. If it's not too hard of a trick, I'll ask the person to do it once more. But if it's a hard trick, then it will have to come out badly filmed and that's unlucky. You can't be perfect all the time. There's a randomness in skating, so you can't control everything. You try to control as much as you can, but at some point you have to take the hit when it doesn't work out. Sometimes the footage doesn't turn out as you expected, or the trick ends up looking a bit weird, but once it’s done, it’s done. I know some filmers who push skaters to do the trick over and over, but I understand how it can be both physically and mentally exhausting for them. So I try not to be a pain and just have a good time.

GC

You also do a lot of special effects in post-production, like the glass breaking for the ACE x Carhartt WIP clip. How did you learn that?

RB

In addition to filming, I work in special effects and motion design. I try not to mix the two often, but I enjoy it every now and then. I learned it by myself, watching YouTube tutorials, and also at my first job. I actually saw some social media backlash on that glass breaking, with Maité hitting the window. One group of people didn’t understand that it was an effect and thought it was awful for someone to do that just for a skate trick. The other group were pissed that it was fake. Maybe I should have been more obvious that it was fake? The first clip from the collaboration is a fisheye breaking, with the cracks forming the ACE x Carhartt WIP logo, so I thought it was clear. Perhaps it was presumptuous, but I saw it as a nod to the film Un Chien Andalou by Luis Buñuel – in the opening scene, a woman's eye is sliced open, signaling to the audience that they are about to enter a dreamlike, surreal world.

GC

Yeah, you just know that you're not doing that trick and ending up with a broken window like that. I would be more worried about the people that thought you guys were breaking a fisheye and turning into a collab logo.

RB

Some people want skate videos to be really raw and don't want the footage altered. But through the way you film, what you choose to film, and how you edit, it's already far from raw. It's going through your spectrum as a filmer, editor, or director. So nothing is completely raw. A lot of people don't realize the time it takes to film a four-second clip. The ratio of filming to what we keep is crazy. But people might not know that, unless they skate.

GC

Do you ever think that one day through phones, filmers with proper cameras will become obsolete? Especially when some people might want to upload clips immediately that day on Instagram, whereas with a camera, it might not get seen for a long time.

RB

It’s nice to have both and I think it will stay like that, as they both offer a different look and outcome. I used to want to keep everything on the camera, but I’m more relaxed with that now. It’s also good for skaters to post phone footage, as it feels more casual. These days, with Instagram, skaters are their own managers – curating their image, what to post, and how to post it. Sponsors often require a certain number of posts per month, so it’s become a part of their job. For most skaters, though, they’ll still want the best tricks filmed for a proper video.

GC

I’ve heard that you came up with a way to pull apart an AirTag and glue it into your fisheye. Is that true?

RB

I wish! The fisheye has no space, but I did manage to put one inside my camera. And I didn't dismantle an AirTag, I just took away the speaker and put it inside the handle. I also have one in my bag, which I keep locked all the time. I’m a bit of a psycho with that, but there're so many stories of people having their gear stolen, so I like to make sure it doesn't disappear. I lose the Xtreme, I lose my job.

The Bee Whisperer

Meet Harold Barrington Chang, from Toxteth, Liverpool by way of Jamaica. He owns five inner-city colonies, home to over a million bees. Known for his unorthodox beekeeping methods – such as forgoing any protective gear – ‘Barry’ exhibits a fearlessness that is perhaps more akin to faith.

Words: Thomas Gorton

Images: Kieran Ashton-Jones

When Harold ‘Barry’ Barrington Chang was a child in Clarendon, Jamaica, he would often lay out on the grass to watch bees flitting in and out of their hives high up in the trees above. For an hour he could watch them, transfixed by the rhythm of their gentle industry; a perfectly-functioning insect city steady at work. “No fuss, no fight,” Barrington Chang says. “They just kept coming and going, coming and going.”

Now aged 75, Barrington Chang lives over 4,500 miles away from Jamaica, in Toxteth, an inner-city area of Liverpool, but his early meditative appreciation of bees managed to follow him across the ocean, and even define his life. Today, Barrington Chang owns around 50 hives; each home to somewhere between 20 and 30,000 bees, which makes him the custodian of over a million flying insects. Barrington Chang’s methods might feel a little unorthodox, even to beekeepers. Shunning protective gear, he goes as far as routinely stinging himself with his worker bees, adamant that their venom has medicinal benefits, specifically for his arthritis. (He might be onto something: scientific trials are currently underway into whether bee stings can help treat Alzheimer’s.)

Barrington Chang first came to the U.K. twenty-five years ago. He had never left Jamaica and having “worked hard and raised kids until I was 50,” was seeking some kind of new life. First, he went to London, but finding the intensity of the capital too much, he soon headed north to Liverpool, a city he now considers his home. Barrington Chang had taught himself a lot about looking after colonies in Jamaica, but he still regarded himself as inexperienced when he arrived in the UK, and so he joined the British Beekeeping Association. “I took some exams and learned a lot,” he says. “How to breed the bees, how to breed my own queen, how to find out if the bees have a problem. You can detect a problem in a hive, and work out what you can do to help. When I started I didn’t realize this, but I recently found out that my grandfather also kept bees. I feel like it’s in my genes.”

In 2016 Barrington Chang found local fame through an escapade involving a swarm of bees in a city center pizza restaurant. Alerted to the swarm by a friend, Barrington Chang arrived at the scene and, using only a cardboard pizza box and a smoker, managed to coax the bees into his car, then drove them back to his house. Since that moment, he’s been known in the Toxteth and Dingle areas as “The Bee Whisperer”, one of those mystical neighborhood figures, a lone ranger adored as much by shopkeepers as he is by lads riding the streets on bikes on account of his unique occupation – he’ll collect any honey bees, any time, for no charge.

Today, Barrington Chang’s hives are spread out across three locations. One is on the roof of the John Archer Hall, a building in Toxteth named after the country’s first Black mayor, which Barry loves for its panoramic views of the city and its cathedrals. Another is adjacent to a basketball court over the road from Liverpool’s African Caribbean Centre, which is currently under threat. And the last is in the backyard of his home in Toxteth, a small concrete square packed with hives, where the bees buzz around us as we stand to watch. It’s an overcast, winter’s day in South Liverpool, but Barry’s gentle enthusiasm for his colonies and their work is warm. He pulls out a honeycomb, encouraging me to press my thumb into it so that golden liquid gushes out of it. “Take care of them, and they will take care of you,” he says, and they do – Barry regularly gives his own-branded honey away to the community.

Inside, we take a seat at a small dining table in the corner of his living room; an intimate space brimming with mementoes of his life – framed photographs of his three children, framed newspaper clippings about his beekeeping hung on the walls, Bob Marley records, an acoustic guitar. Here Barrington Chang talks in a soft but passionate voice about the relationship between bees and Rastafarianism:

“As a Rasta, I don't know two loves, just one love. The love that I have for my mother is the same love that I have for your mother, is the same love that I have for you, is the same love that I have for the bees. I have the principle of one love – I like that principle and I work with it to this day. If you go to the bees with an aggressive mind, a mind that is not loving, the bees can feel it. The bees know. But if you go to the bees with a warm, loving heart, then the bees will do the same for you. That's why I work with no gloves, no suit, even though everybody wonders why.”

He passes me a piece of ‘bee bread’, a tightly condensed lump of pollen that bees create in order to feed the hive. Chewy and relatively tasteless, Barrington Chang swears by it as an immunity boost, and uses it to treat people in the local community who suffer from hay fever. “I cure man who said he have hay fever when he was a little boy,” he says. “Growing up, his parents couldn't keep flowers in their house. When I cure somebody, I tell them ‘anything you couldn't do, go and do it now’. One man told me he didn't know flowers smelled so nice.”

In 2010, Barrington Chang’s peaceful life in Liverpool was marred by the Conservative government’s brutal policy of targeting, detaining and attempting to deport Commonwealth immigrants. He was taken to Wavertree Police Station, then to Manchester, then to London. He was kept in Oakington detention center in Cambridgeshire for three to four weeks, and then one day they called and sent him back to Liverpool. Barrington Chang still doesn’t know why he was released this first time.

In 2012 he was detained again for six months, in a center in London that he describes as a “high security prison”, a hostile, enclosed space where he had no privacy. “Horrible experience man,” Barrington Chang says. “People just keep watching you, you can't go around, you can't move around. It's just like in a prison.” Barry appealed, and wrote letters to the then-Home Secretary Theresa May and to the Queen (who replied to Barry and told him she was looking at the case). His case progressed, however, and he had been assigned a plane with specific details – the time that he would be deported, and the time that he would land in Jamaica. At the very last minute, though, before getting on the plane, he found out that he’d won his appeal. A brutal, inhumane experience of being detained and forced to wait in purgatory; Barrington Chang says that he went into the detention center healthy, and came out on crutches. “They don’t cater for vegans in there,” he says. “They gave me chicken and rice, which I refused. They said I should take the chicken off and eat the rice. I fell down because for many days I didn’t get no food to eat. It was starvation. I had a slipped disc that got worse and worse.”

Now Barrington Chang faces another battle: the fight to save the African Caribbean Centre in Toxteth, which the city council are suggesting be demolished in order to build a new school. Barrington Chang has taken me to see the centre, and as we stand inside a vibrant space with an unassuming exterior, he reflects on how it has been an integral part of his life, as both a sanctuary for his bees, but also in helping him settle and integrate into the wider country. “The Caribbean Centre is the first place that I meet Caribbean people,” he says. “The centre represents us – we have our Caribbean culture, Caribbean food and Caribbean music. We used to go all around the country to play domino tournaments, it’s how I got to know a lot of places in England.”

We leave the Caribbean Centre and wind our way through Toxteth to the John Archer Centre. This inner-city area is a vital part of Liverpool’s history, as the scene of 1981’s riots that began due to longstanding tensions between police and the black community, sparked by the arrest of a Jamaican-born man named Leroy Cooper. At the centre we hike several flights of stairs up to another collection of colonies, kept in an unusual rooftop garden situated on top of a community building that also hosts drumming workshops and dance classes. When discussing injustice, Barrington Chang points to the utopian harmony of his hives as a method for human living. “We must live together in unity no matter what color, what creed, what nation,” he says. “That's the system we must use to live together. Take bees; one hive of bees with one queen laying all the babies. When I look at them I see black bees, red bees, brown bees. All of them work together in that colony in unity and strength, and they don't make no trouble. So why can't we learn to live in oneness and love for everyone?” We part ways on the top of the John Archer Centre, overlooking the whole of Liverpool, while behind us the bees buzz gently as they go about their work; a city within a city, high up in the sky.

Suea

You may know her for her playful, referential food creations – Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair as onigiri or cherubs shaped from mounds of butter – but Suea has already pivoted. Driven by a restless curiosity, the Seoul-based multi-hyphenate explores the delicate balancing act of combining passion with profession.

Words: Holly ConnollyImages: Chanhee Hong

It doesn’t take long in conversation with Suea to become aware of a certain restlessness in her, a drive to keep looking for what’s next. At only 31 years old, she has already been a fashion buyer at Opening Ceremony, a food stylist whose delicate, otherworldly creations garnered a sizeable Instagram following, a founding member of a cafe and home goods store in Brooklyn,, and now consultant for a beauty brand. “I have no patience. I have no tolerance for slow,” she says. “I just need a change every few years. I have so many things that I want to do. I can't do the same thing for too long, but I will ultimately always return to my obsessions.”

We are speaking over video call. Suea is in Seoul, where she moved this past August after nine years in New York. Planned as a three month stint consulting, it now looks set to be a more permanent move, as she commits to working with the brand. It is also in some ways a return to home – Suea was born in Korea, where she lived until her family moved to Montana when she was five, then on to New Jersey with her mother after her parents’ separation. “I've wanted to live in Korea for my entire adult life, but never really had the chance,” she says.

Here she discusses the phenomena of food culture on Instagram, the parallels between food and fashion, and her dedication to beauty.

You started Suea’s Dinner Service in 2019, while still working at Opening Ceremony. Why did you want to move into food?

At that point I had been at Opening Ceremony for three years. It was a dream job, but after a while I felt like I was giving so much energy to my job that there was nothing left for me. I had always really loved cooking, from when I was a teenager. My mom only cooked Korean food at home, and everyone at school, including my friends, were white or non-Asian. I was like, “I don’t want Korean food.” So my mom said, “Okay, then you can make something.” That’s how I started getting into cooking.

I never thought I could make money doing food, nor did I really want to. I had been so obsessed with fashion growing up, and then after working in fashion for a few years, I could feel my love diminishing, I thought, ‘I can't let that happen with food’. People would say, like, “Why don't you go work at a really nice restaurant and learn?” I would say, “No, because the minute I start working at a restaurant, I'm not going to want to cook anymore.”

What is your relationship to fashion like now?

It’s funny, when I got really into food, and was freelancing and making money off it, I got really obsessed with food culture and nice kitchenware. I would spend all my money on expensive knives, because I was so sick of fashion at that time, after working at a fashion company for so long. Now I'm obsessed with clothes again, and I’m sick of food stuff. That's ultimately what happened with food. I loved it so much and made money off of it, and now I think, ‘Great. I need a break’

You’ve worked across industries. How would you define yourself and what you do?

I don't know how I would define myself. Right now, the new chapter in my life is brand development, and I’m learning a lot about the beauty space and lifestyle products. That's ultimately why I decided to come here to Korea, because it's all new and exciting. It was weird being called a chef, I would think, ‘I don't work in a restaurant.’

I think food has become a really interesting, strange space, especially because of Instagram. There are now people who are not ‘professional’ in the sense that they have experience of working in a kitchen, who can blow up on Instagram.

My nightmare would be to be called an Instagram chef, or an ‘Instagram food girl.’ I think that's ultimately why I got tired of doing it. I thought, ‘People probably look at my page and wonder if I even cook well, because it's pretty and cute. Which was so funny, because my close friends or my boyfriend know that I don't make Instagram-friendly food most of the time. It’s just good, home-cooked meals. It got really exhausting having to think about Instagram in terms of my food. It was like, “This is getting dark.”

Something that runs through everything you do is a dedication to aesthetics. Where do you think that comes from?

I definitely care a lot about how everything looks. There's no ‘why’ in terms of things having to be beautiful, I just think it makes life better if they are. I think that drive is something that you're born with. My dad is an architect, and I didn't really grow up with him, but I’m spending more time with him here because he lives in Korea as well, and it's interesting, because I'm thinking, “Oh, I guess maybe I got it from you.” My mom also studied art history and so, especially for Korean immigrant parents, they were more supportive of us doing creative stuff.

Do you see any parallels between food, as an industry and space, and fashion?

I think they're both very vicious industries. They both really overwork their staff, and the work culture is similar in both, how obsessed people get with their jobs. I think that they both also take things too seriously. Sometimes in fashion it would be a nightmare, tears, just a shit show. I would think, “Wait, all this for what? A skirt that we're going to sell for three months, put on sale, and then sample sale and then throw it out?” With food it’s the same thing, all the nightmare kitchen stories, for dinner? It’s not that deep.

They're both very customer-focused in a way too, more than other creative disciplines they’re very centered around immediate feedback. And they’re both sort of a luxury version of a thing that’s essential.

Yeah, I also see both sides. As someone who has worked so hard in these industries I don't want people to say, “Oh my God, it's just a T-shirt, calm down.” Because I understand why things get so tense sometimes. Ultimately, brands within fashion and restaurants really do change history, they change how people perceive things, which is what makes them so interesting. I think branding – whether it’s fashion, beauty, lifestyle, and even restaurants – is where my heart will always be.