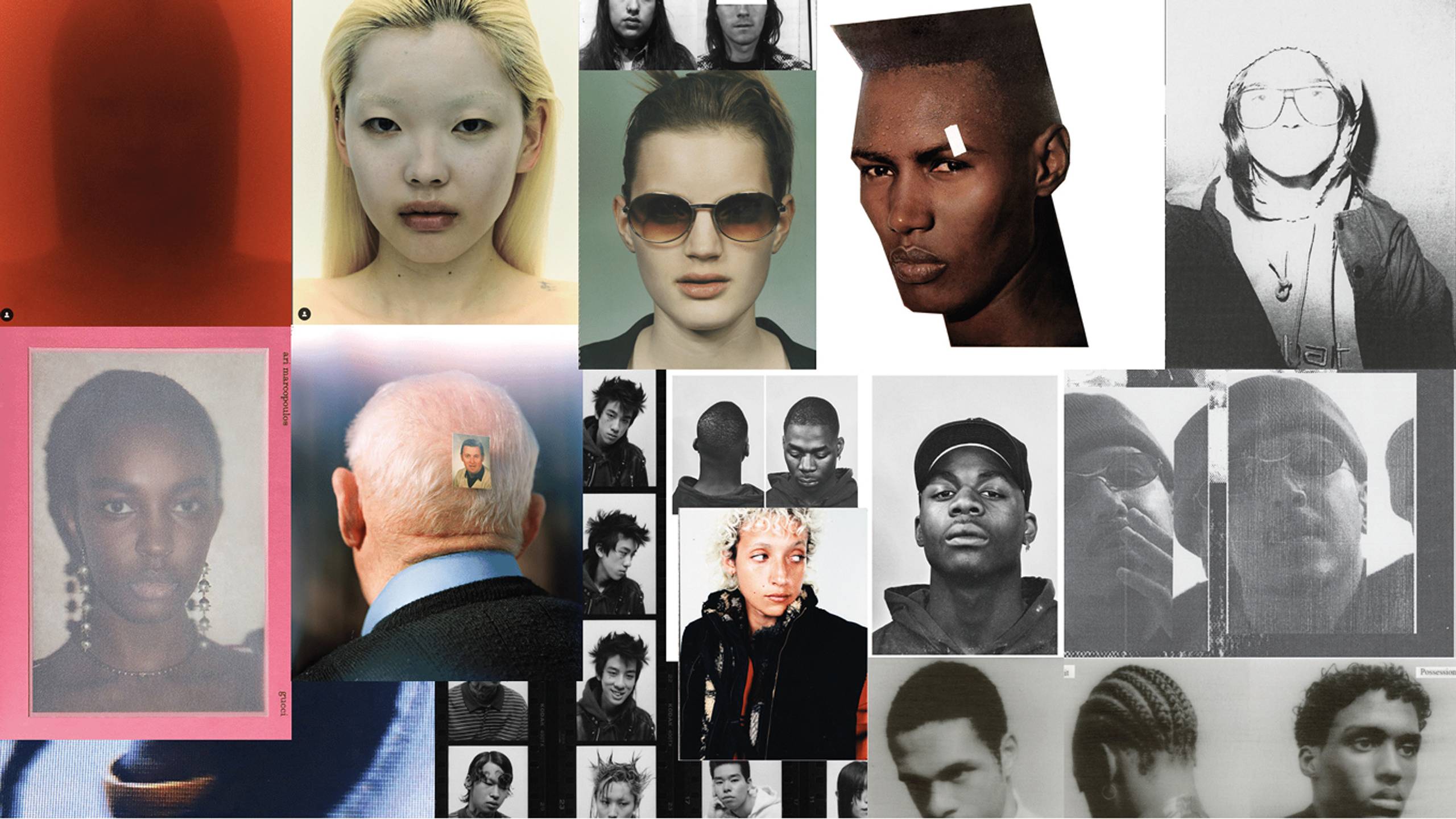

Spheres of Influence

A catalog of contemporary culture, expressed through physical form.

Words: Calum Gordon

It was while editing the last issue of this magazine, specifically an interview with Tokyo-based cultural theorist W. David Marx, that the seeds were sown for the theme of the issue you’re now holding. “In the 21st century, so much of cultural activity has become detached from material possessions, because now it plays out on the internet,” he told Adam Wray. “When I was in college, I was buying CDs and records; I have them, and you can see them when you come to my room—there's all this material expression of my music fandom. Then, suddenly, I've got an iPod, and it's got 1000 songs on it, and no one knows what they are except for me… Music, when it’s dematerialized, becomes harder to anchor your identity to, to show other people, ‘This is who I am.’”

Marx’s analysis feels broadly correct. So much of what we consider ‘culture’ now only exists in digital form, divorced from material reality. But it is an analysis that also feels at odds with the present moment, one in which physical artefacts appear to be enjoying a renewed appreciation. Art books abound. Fashion titles from London’s print media heyday are currently enjoying resurrections and retro-spectives. Would-be archivists are trawling Japanese auction sites in search of rare publications and associated ephemera for boutique stores that continue to open– and presumably make enough money to pay the rent. Most brand events now feature a hand-crafted hi-fi system of some sort. Some artists are releasing folky, hand-crafted goods; others are publishing tomes largely filled with images from their iPhone camera roll, creating a sense of intimacy with the viewer, something that hints at an interior life, however curated it might be.

In fact, what once would have been considered ‘throwaway’ imagery – YouTube screenshots, old scans, images found online – has become an entire subgenre of book publishing itself. Digital ephemerality transmuted into physical form. These books can be built around just about anything: the labels found inside the neckline on old outdoor gear, old Prada campaigns, 90s Paris rave flyers, football hooligans scrapping in fields.

This collective cultural fracking is created with a zine-maker’s impulse, but the form is less ephemeral. Beneath the surface of it is a sort of cultural cataloguing carried out with the fervor of a doomsday prepper, as if the internet might be switched off tomorrow. This instinct is perhaps understandable: anyone who has witnessed the internet’s slow decay in recent years will have detected a pronounced sense of impermanence that previously seemed unthinkable.

A few years ago, much of this energy was directed towards a different medium: t-shirts. But perhaps signposting one’s taste in such an obvious manner is now considered uncouth. It’s notable that one of the best of ‘brands’ of that era, Boot Boyz – whose t-shirts often contained four or maybe five hyper-niche references – have also recently pivoted to print. This morning, as I scrolled Instagram, I saw someone selling a pack of Camel cigarettes with a Nan Goldin print on them. This pack was specially commissioned in 1999 by the tobacco giant, and sold in only clubs in New York Chicago. Now the price was over 300 dollars, and it sold within minutes. Later that day, I stumbled across a cassette tape of two Mike Kelley performances from the 1980s – also sold out. None of the above is a bad thing. Actually, it’s good that people are seeking out culture that cannot be easily consumed on the internet, or preserving the culture that does exist on the internet. It’s good that people are making things and releasing them into the world. It’s good that there’s a renewed appreciation for the physical form. In many ways, it’s liberating that so many feel empowered to try and leave behind some mark, beyond a digital footprint. It’s just interesting when so much of it happens at once. It is sometimes hard to not be cynical, or shake the feeling that this is all merely a trend. As the following 32 pages hopefully show, it is not a trend. Across four major cities – London, Shanghai, Paris and NYC – we have invited a host

of creatives to share one object that means something to them. Something that has helped inform their outlook, or which they encountered at one of those crucial, formative moments, when your own identity is still just one of a series of rough drafts

Stories and conversations spill forth from these chosen objects: discussions of diasporic cultures leaving an indelible mark, in reggae clubs in Edinburgh and on the streets of Paris. The material nature of hip-hop culture is explored in two forms: a humble 3D printed chain and a ‘FREE PIMP C’ t-shirt gifted by Bun B. There is the gift of a Walkman CD player from a father to his son, who would go on to found his own radio station because of it, and a cello bridge that’s never been played. A plush toy sits alongside a family memento, alongside some wire headphones. Every object chosen is the jumping off point for a story or conversation. So, what exactly did we hope to achieve? At times, it felt like a grown up game of show-and-tell. But during the process, throughlines emerged that felt like they spoke to our present moment – one characterized by a certain techno-pessimism and object fetishism. Objects, these silly little things that we hold onto, are often how we make sense of our place in the world. They can be a kind of physical memory, a story. And all that we can really leave behind are the stories that we tell.

Esteban Scott – Plushie

Esteban Scott is an apparel designer, musician and photographer based in New York City. As the founder of Cliff Creative Projects, a clothing brand and creative house, he operates with an ethos of community and collaboration, understanding that the best ideas are those shared with friends. For our conversation, he brings along Jafa, a plushie toy he’s designed. Soft, mischievous and full of big ideas, Jafa is, in a sense, an avatar for what it feels like to live, love and play in a city where everyday is an adventure and every encounter an opportunity for creation.

Images: Nuvany David

Words: Isabel Ling

Isabel Ling

Let’s start by introducing Jafa, who is he?

Esteban Scott

I made him a few years ago. I got a chance to work with my friend Moya [Garrison-Msingwana], who's one of my favorite illustrators and artists. He depicts characters with a really interesting sense of proportion. So I thought he’d be perfect to build this character with. It’s been a long time coming, but this is my sample. I wanted to work with different animators and really just bring this guy to life before we release him as a plushie. He has a super big head. I wanted to do that on purpose, because it’s representative of having a bunch of ideas. He’s this mascot for living your life creatively, having all these weird ideas and being a problem solver. So that's kind of the idea behind his big head.

Isabel Ling

Were there any cartoons that you grew up watching that influenced the design?

Esteban Scott

He's definitely inspired by Rocko’s Modern Life. He’s a little goofy, like Hey Arnold -style. He’s supposed to be somewhere between a dog and a dragon-lizard, you know. And he has those big ears, and when he flaps them, he can fly.

Isabel Ling

I know that you’re a clothing designer too, what inspired you to make a plushie?

Esteban Scott

Well, I feel like my favorite time in style and culture would be the late 90s and early 2000s. So I’m returning to some of these ideas now that I’m of age and have these resources and an understanding of production. I'm trying to keep that spirit always alive through the clothes or through the music. I feel like doing a plush and creating this character is still very aligned with that. I got a lot of inspiration from NIGO and the way that he did Baby Milo. Like BAPE was the brand, and then there was this sub-brand with this character. I would love to see Jafa with Astro Boy, or Sponge Bob, or something like that down the road.

Isabel Ling

Yeah, I could definitely see him as a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon. How did you envision Jafa’s personality when you were designing him?

Esteban Scott

I feel like Jafa touches on a playful, youthful spirit. He's witty, he's welcoming. I saw this really funky drawing at the park in Tokyo. It was this kid on a bike, a very wobbly drawing, it almost looked like it would be like graffiti, but it wasn't. And in the drawing, he has this speech bubble. I asked my friend, “Yo, what is this guy saying?” And he told me it means, “Everyone is welcome.” I just really resonated with that, and kind of referenced that.

Isabel Ling

Jafa really calls back to a younger self. If you could give your past self advice, what would you say?

Esteban Scott

I would say, trust yourself, respect yourself, and respect time. Don’t waste it, because looking back on it, I’m super proud of the body of work, but I think I've always been like, hungry and thinking about going bigger and what if I could go do more? So yeah, I would just tell young me, don’t wait for that, just keep going.

Same Paper – Cap / Cello Bridge

When Same Paper was founded in 2013, initially it, “Felt more like a sharing platform; a space where we could share books we liked and content that we found interesting,” its founders, photographer Xiaopeng Yuan and graphic designer Yijun Wang, explain via email. “It was like a hobby group, purely for fun and to satisfy our own desire to share. But over time, we began to want to bring some fun, creative ideas to life and put out content that we were truly passionate about.” Today, the Shanghai-based creative studio retains that core ideal, which manifests in a sincere appreciation of printed matter and photography, while continuing to evolve. Same Paper release products, from considered sportswear to playful objects – like a candle modeled on a stack of books on a shelf. They also publish books, working with photographers such as Jack Bool, and a magazine titled Closing Ceremony. In between all that, they find time to do the usual agency stuff: working with brands and artists. Both of Yuan and Wang’s chosen objects, however, hark back to the studio’s earliest days: a cap – one of the first items they ever produced – and a strange wooden object that we had to reverse image search to identify.

Images: Sirui Ma

Words: Calum Gordon

Calum Gordon

Tell me about the first item you picked – the Teller cello bridge – where did you find it and what attracted you to it?

Xiaopeng Yuan

Years ago I was a huge fan of Juergen Teller’s photography and was passionate about collecting all of his photo books. I first came across this symbol in his book Zim mermann, which I bought over a decade ago. At the time, I was simply drawn to its shape—I even thought it might be a personal emblem or motif of Teller’s. It wasn’t until a few years ago, when Teller collaborated with Palace and used the same object on a sweatshirt, that I truly became curious about what it actually was. That’s when I learned it was simply a common tool used with cellos—a bridge. After understanding that context, I grew to love it even more. I genuinely admire its form. Every time I see it, I’m still amazed by the design and how it functions so precisely.

Calum Gordon

Do either of you play the cello?

Same Paper

Nope.

Calum Gordon

What does the item represent to you?

Xiaopeng Yuan

Looking back, there’s something truly beautiful about getting to know an object in such an accidental and circuitous way — it’s the kind of feeling that stays with you for a long time. It serves no real purpose — it’s just a small keepsake, a little object of remembrance.

Calum Gordon

Same Paper is best known for its work within print. What are your early memories of being attracted to books or magazines?

Xiaopeng Yuan

I think it’s a process where the joy unfolds gradually through interaction. When I first started looking at photobooks, it was simply about the pleasure of holding one in my hands and enjoying the images — I saw them as a way of collecting visuals, much like opening a folder on a screen today to browse through pictures. But as I went deeper, I began to notice the nuances in editing, the logic behind the design, the choices of material — and slowly, I realized that every detail in the object was a reflection of the sensibilities of that distant artist I admired. That realization, that quiet dialogue between you and the artist through the physical experience of flipping pages — it stays with you.

Calum Gordon

Are there any publications that you own that are particularly special to you?

Xiaopeng Yuan

I tend to gravitate toward the artist books, photobooks, and zines I came across early on — especially books published around 2010 or earlier. The first ones that come to mind are Wolfgang Tillmans’ and Juergen Teller’s early publications. Books by Paul McCarthy and Jason Fulford. The very first zines I got, like the Werker publishing project. I feel that many books released after that time often seem to follow an editing or design approach that mirrors the way content is quickly consumed and understood on social media. It gives you the sense that just knowing about it is enough — there’s no real need to actually own the object.

Calum Gordon

You have also included a cap in your selection. Can you tell me about it and why it’s important?

Xiaopeng Yuan

We pretty much wore this hat all the time. Later, when we produced a small batch, we were surprised to find it became popular. People who might not have been that interested in books ended up discovering us through the hat instead. Not just at art book fairs — we’d sometimes spot people wearing it in everyday life too. That feeling is kind of magical. The process of developing these products is definitely complex — there are so many unpredictable factors. But we embrace the mindset of a hobbyist. It’s a continuous process of learning, trial and error – as well as small but fulfilling moments of satisfaction.

Calum Gordon

Can you tell me a little about Closing Ceremony magazine?

Xiaopeng Yuan

For us, Closing Ceremony magazine has always been a visual storytelling magazine with more freedom in its themes and direction. At the beginning, we defined it as a photography magazine— born out of the observation that many photography publications at the time felt overly serious, and often carried a certain ambition or formality. We wanted to create something different — a photography magazine that we ourselves would genuinely enjoy. The name Closing Ceremony comes from the mechanism of a DSLR camera: each time the shutter is pressed, it’s a ceremony that opens and closes — a beginning and an end. The name also serves as a kind of tribute to an older generation of photographers. At the same time, it carries a slightly melancholic tone — not overly passionate or loud.

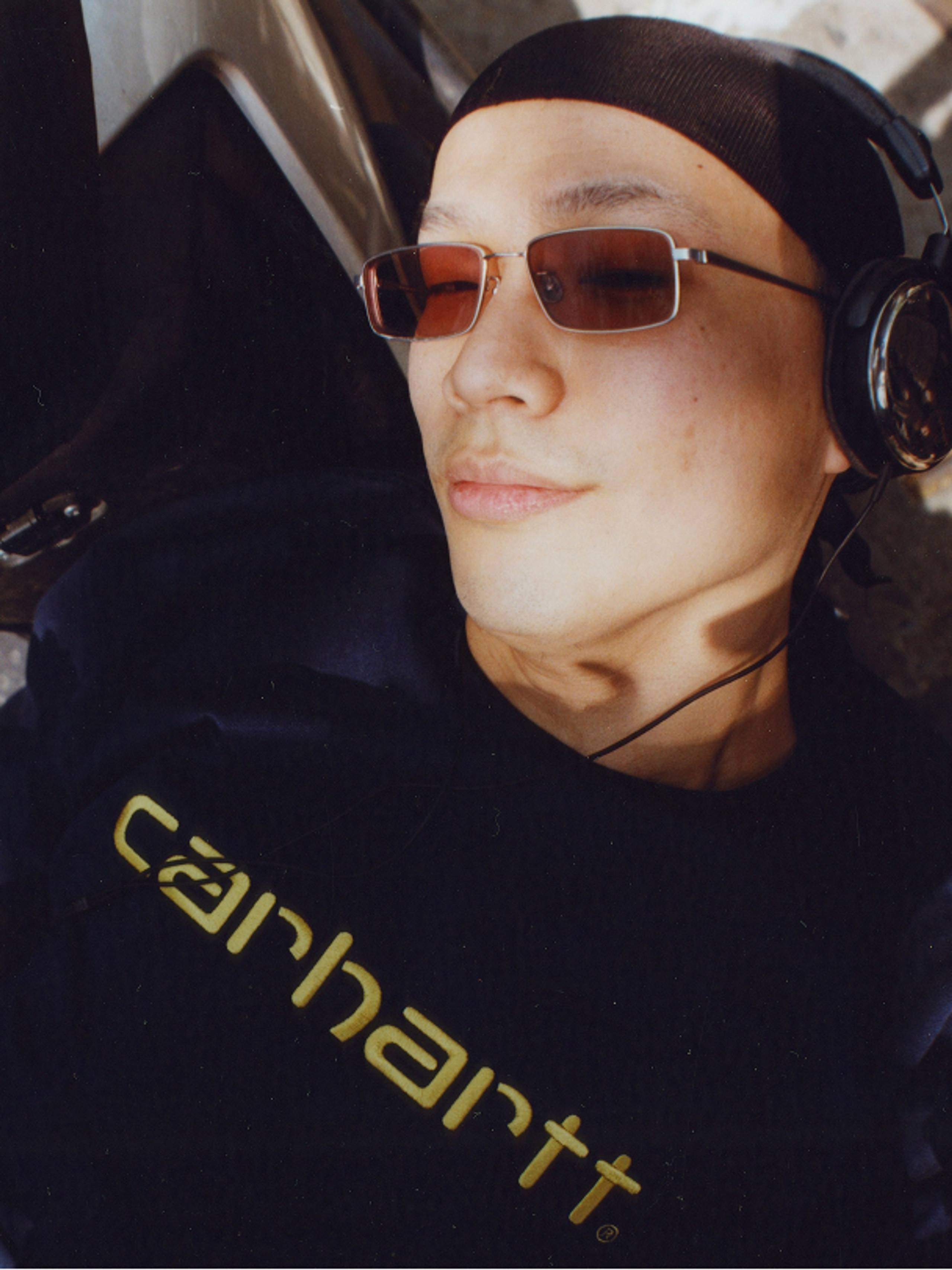

YB – Walkman

Music has long been the pulse of Shanghai’s youth culture and its creative scenes. While this was once found in the city’s clubs, which helped nurture underground movements, today it is defined by a new wave of creatives and collectives, carving out their own spaces. Of these, byyb Radio has quickly become one of the most recognizable. byyb’s founder, yb, was born and raised in Shanghai. After spending almost seven years studying abroad, he returned home and launched byyb at the end of 2023. It started with a tiny spot outside a bar – “I invited four friends to play DJ sets,” says yb – then moved into a former fruit stand. Today, just over a year later, byyb Radio has collaborated with over 400 artists and DJs from China and beyond—amplifying local voices and connecting them to the world. For this feature, yb chose a SONY CD player—a small but meaningful object that accompanied him through the early steps of his music journey, serving as both a medium and a muse.

Images: Xuzhaopei

Words: Didi Hu

Didi Hu

Tell us about the object you brought—a SONY CD player. How did it come into your life?

yb

If I remember right, my dad gave it to me when I was in the sixth grade. Back then, it felt like cutting-edge tech. Because of it, I started buying and burning a bunch of CDs—mostly pop from Hong Kong and Taiwan. That stuff really became my friends' and my emotional sustenance at the time. Later, when I was studying in the States, I stayed with a host family. Their kid leant his whole music collection to me—everything from rock, country, and pop to metal. I’m talking Madonna, Justin Timberlake, Christina Aguilera, Jack Johnson, Beck, Cypress Hill, Coheed and Cambria. That was my real musical awakening. When I got back to China, I kept buying CDs—local artists like Jay Chou, David Tao, S.H.E, and even older names like Dao Lang, A Du, Andy Lau. My taste was, and still is, all over the place.

Didi Hu

What does the CD player mean to you now?

yb

To me, it’s never been just about a specific genre—it’s about the machine that plays the music. There’s something multidimensional about it. It’s not just about songwriting or mixing, but also the technology behind it, the engineering that makes it possible. People often forget how much work goes into making music listenable. Like, that CD player didn’t just appear out of nowhere—it took a lot of people, a lot of craft. Even recording a song in a studio involves so many invisible steps. That whole process has always fascinated me.

Didi Hu

You spent over six years studying in the US, where you majored in mathematics. How did you end up diving into music production?

yb

Yeah, I’ve always loved music, but it started out as a hobby. A few of my best friends from college moved back to China and started the hip-hop group Straight Fire Gang there. At the time, I was still in grad school and feeling a bit lost. But hearing their songs really lit a spark in me. I just had this sudden thought—why don’t I go back and make music with them? I didn’t know the first thing about music production. So when I came home, I started teaching myself. I remember spending a whole week learning how to use music software, and then I made my first beat for them. Looking back, that was probably the most ‘original’ I’ve ever been—no overthinking, no influence, just pure instinct. And people liked it.

Didi Hu

There’s something beautifully open about byyb—it doesn’t feel exclusive or gatekept. What was your intention when building this community platform?

yb

Most of the people we invite are deeply rooted in the underground scene. They’re really good at their craft. In the early days, I would reach out myself, but now we also get submissions. Ultimately, I only care that the music is good. Really, what gives me joy is seeing people do what they love—and doing it well. That’s what gives me a sense of purpose. I’m not obsessed with long-term planning. I just want to build more genuine, powerful performances.

Jon Caramanica – Letter / Pimp C T-Shirt

I don’t know how you could ever quantify a sense of boundless curiosity, but following over 7,500 people on Instagram might be as good an indicator as any in today’s era. Officially, Jon Caramanica is the pop music critic for the New York Times — but his zeal for culture extends far beyond the typical requirements of such a role. Maybe this is because it is only possible to truly understand contemporary pop culture if you can parse the various niches that bubble under the surface, each containing dormant potential, ready to be transformed overnight through a combination of happenstance and virality.

Ask Caramanica, and he’ll tell you that this impulse — to not only understand the niches and recesses of our culture, but how they interact and coalesce, often in service of some greater narrative — is something that has always been part of his makeup. This was the case when he was cutting his teeth as a music journalist in the early aughts, writing for titles such as SPIN and XXL. It was the same impulse that led to him searching for a profile on UGK, the seminal Southern hip-hop duo of Bun B and Pimp C, whose idiosyncratic sound would, in time, recalibrate the ear of the average hip-hop listener. Unable to find any writing or interviews to satisfy his own curiosity, Caramanica decided to do it himself — redressing a rather egregious oversight from New York’s litany of rap-focused publications in the process. “It felt important to me to correct the historical record,” says Caramanica. “Why were there a hundred articles on The LOX — who I love — but almost nothing on UGK? That didn’t make sense to me.” Here, he discusses an enduring love of hip-hop ephemera, radically shifting media ecosystems, and two of his most cherished possessions: letters from Pimp C, penned from prison in 2004, and a ‘FREE PIMP C’ t-shirt, gifted to him by Bun B that same year.

Images: Nuvany David

Words: Calum Gordon

Calum Gordon

Knowing you from your writing, UGK makes perfect sense. But also, as someone from New York, coming up in the 90s and early 2000s, the choice feels like a bit of a curveball. When did you first encounter their music?

Jon Caramanica

I was playing UGK records on my college radio show in 1995. We’d get promo copies from Jive, and while I didn’t know much about them at first, I knew the production was great and the rapping was great. But I wasn’t aware of the broader story. As I got deeper into my writing career, I realized they weren’t just one of my favorite rap groups—they were also surprisingly undercovered in the hip-hop press. I couldn’t find a great interview or profile on them from that 90s era, so I made it my mission to write one. One year, I went to SXSW — the first year Bun B performed there [2004] — and I tracked him down, introduced myself, and said, “Hey, you don’t know me, but I’m a big fan. I think what you do is important, and I don’t think you’ve been interviewed particularly well. I’d love to change that.”

Calum Gordon

Do you think that was because they were from the South, which wasn’t a major rap media hub like New York or LA?

Jon Caramanica

It was partly about the media ecosystem and partly about coastal parochialism. New York folks thought nothing was as good as New York. LA folks thought nothing was as good as LA. And for a long time, those two cities only cared about each other as potential competition. That’s not the case today, but in the 90s, UGK was operating completely outside the mainstream media and industry ecosystem. It took a long time for the old guard to fully embrace Southern rap.

Calum Gordon

Back then, there was still this perception that Southern rap wasn’t legitimate.

Jon Caramanica

Right, like it wasn’t on the same level. UGK was unapologetically Southern, and at the same time, they were among the best. As someone from Brooklyn, hearing that and accepting it was a huge moment for me—it opened me up to music coming from everywhere.

Calum Gordon

Even in the early-to-mid 2000s, you could argue that despite their chart success and influence, UGK still didn’t get much media coverage.

Jon Caramanica

Exactly. When I was writing for XXL in the early 2000s, I focused on artists who weren’t from New York or LA—that was what interested me most. Send me to Texas, send me to the Bay, send me to Atlanta—that’s where the energy was. At that point, New York hip-hop had started to eat its own tail. It wasn’t innovating the way it had been. So as a curious listener, I was always looking for what was new, and more often than not, that was coming from outside New York and LA. I pushed through and ended up writing a big piece on UGK for XXL magazine, which led to a relationship with Pimp C. He was in prison at the time, and we exchanged some letters—some of my most prized possessions from my career. I ended up writing the first big profile of him when he was released from prison at the end of 2005.

Calum Gordon

What is your recollection of that encounter with Bun, when he gave you the t-shirt? How did he react to your interest in writing about them?

Jon Caramanica

I think Bun understood intuitively the power that well-contextualized press coverage could have, largely because he’d had so little of it at that point. He was a huge fan and scholar, and I think it irked him a little that the main publications of the 90s didn’t pay UGK much mind. That t-shirt comes from my last day in Houston working on that first UGK piece. Nowadays, everything is merch-ified – you can find shirts commemorating the most minor occasions, or can easily make one yourself. This was a different time. He’d had a local t-shirt printer make a clutch of ‘FREE PIMP C’ shirts that he was going to give out to friends, and I happened to be riding with him as he ran the errand. I was very touched that he gave me one. Not long after that, you began to see the internet flooded with similar shirts, usually unsanctioned bootlegs. But this was the product of intimacy and love and dedication. People who know me know I’m a real collector of ephemera, and also that I wear almost all of my best, oldest rap t-shirts. But this one, I want to preserve. That fragile, handmade, from-the-heart moment – that can’t be reconstructed.

Calum Gordon

What was your impression of Pimp C? Obviously, there are his legal troubles,

which is why he was writing to you from where he was. But I’m interested in the fuller story.

Jon Caramanica

First of all, as a producer, he had an incredible ear. He understood how deeply hip-hop was indebted to soul music, and even further back, to Southern gospel and blues. He heard those connections like a historian would. As a rapper, he was one of the most flamboyant, flavorful, talkative presences in the genre. He had this ability to emphasize certain syllables in a way that could completely change the meaning of a phrase. Plenty of rappers are technically skilled, but not every rapper can manipulate words like that—where a tiny shift in delivery alters the whole feeling of a line.

Listening to Pimp was like seeing someone paint with a totally different set of colors. He was a rigorous MC, but also an expressive, almost abstract one – which is the direction so many successful rappers have taken in recent years. He really paved the way for that style.

Calum Gordon

This story is as much about media ecosystems and how they change over time. I feel like we’re in an era where things are beginning to shift, again – particularly with how celebrities engage with media, or how emergent stars seek to shape their own narrative with new tools and formats available to them. Where do you see that heading?

Jon Caramanica

I think we’re in the middle of a grand recalibration of what media even is. But an independent press, beholden to no one, will always be preferable, even if it’s harder than ever to pull off and

scale. I see sharp and curious people online every day – making TikToks, recording podcasts, making memes, conducting interviews at an artist’s earliest stages. But I hope, when everything shakes out, that the same things still matter as when I was getting into the game: a palpable sense of curiosity, dedicated knowledge, a novel perspective, and ferocious independence.

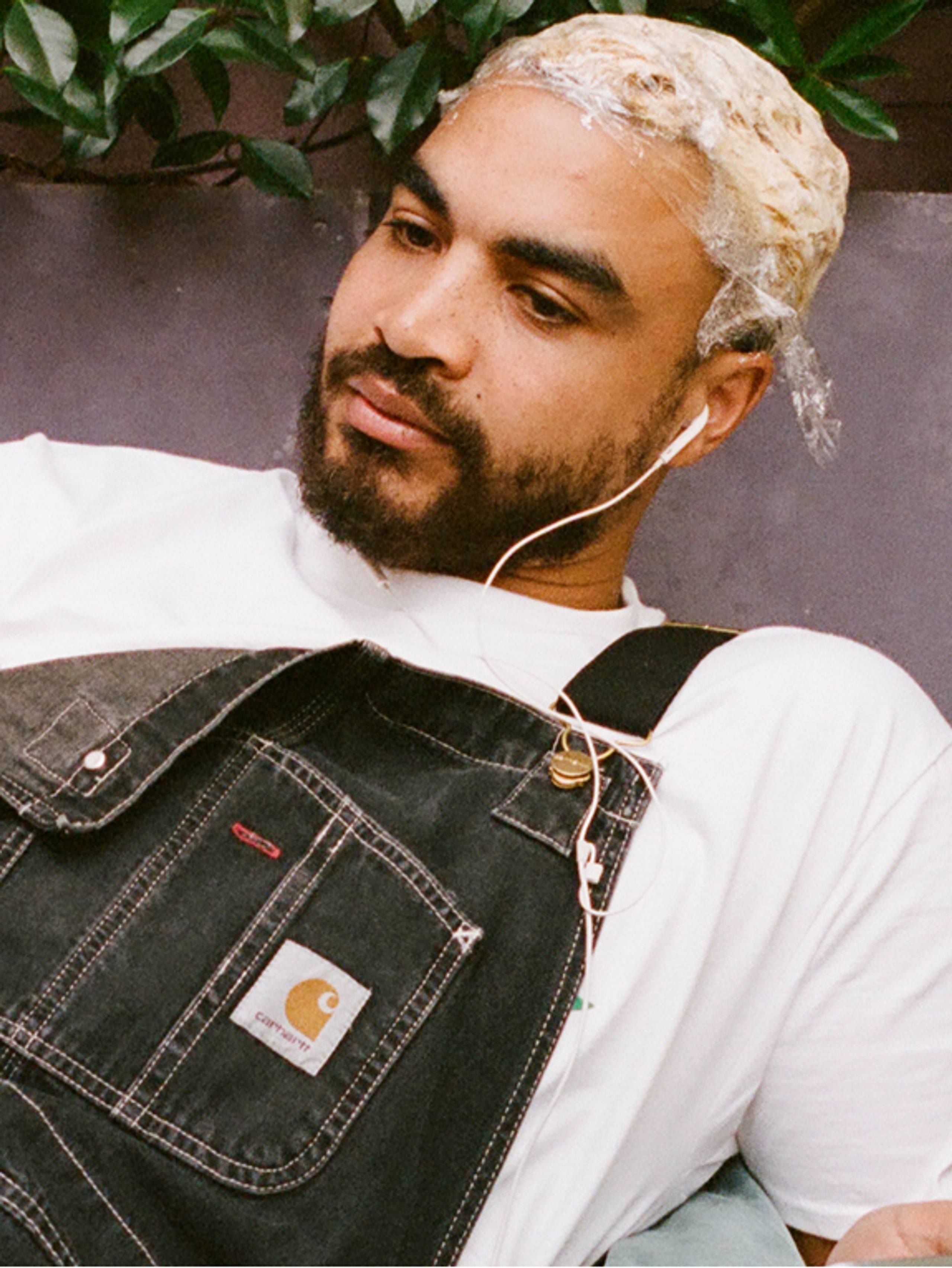

Implaccable – Chain

It is little over five years since Paris-based rapper Implaccable first began releasing music, but a cursory glance at his discography soon reveals his prolific nature. There are a slew of singles, mixtapes, and EPs, as well as full-length albums, such as 2022’s So Vladdy or the more recent Sans frontière toute la Terre [Without borders the whole Earth]. Across this body of work, one motif recurs: the almost reflexive refrain of “TRACS.” When I speak to Implaccable via video call, the same word appears again. This time, on his chest, in the form of a matte black convict mesh chain, with three spikes on every other link and a large ‘TRACS’ pendant, with a font reminiscent of the film Sin City. A chain, in the context of hip-hop, can represent many things: a right of passage, a skewed materialistic outlook. But with Implaccable, whose own version has been prudently 3D printed, it appears to reflect both a way of life and a crew.

Images: Laurent Segretier

Words: Martin Sigler

Martin Sigler

You garnered attention by sampling the zouk classic “Ancrée à ton port” by Fanny J on the track “Tracs Fanny J” from So Vladdy . Would you describe your music as ‘sample drill’?

Implaccable

When I started out in Guadeloupe, I was doing trap music. It was when I arrived in France around mid-2020 that I started doing sample drill, which evolved into Jersey drill and Jersey club. The particularity of this genre is that it transforms samples from iconic tracks into fresher and faster productions that tell a different story. That’s what I did with ‘Tracs Fanny J.’ This way, you convoke a collective memory while affirming your own style.

Martin Sigler

‘TRACS’ appears as a recurring motif in your discography. What does it mean?

Implaccable

Originally, I created the acronym ‘TACNA,’ which stands for ‘Toujours Aller Chercher Notre Argent/Amour’ [Always Go and Get Our Money/Love]. Over time, I realized that, as it is made up of two syllables, it was difficult to include it in my tracks. So I replaced it with TRACS, which is easier to use.

Martin Sigler

When did it become a chain?

Implaccable

When we started to have shows, I realized that it was important to have a recognizable sign that would express who I am. I contacted the jewelry designer Koan Asaky, whose anime style I like, and we designed the pendant typeface to fit his standard chains. Wearing a chain is common in hip-hop culture, but I must say that in the French underground scene, I'm standing out.

Martin Sigler

Chains are a symbol of social status and/or a sense of belonging to a group. They are often ostentatious and shiny (cast in gold, set with diamonds, etc.). Does yours deliberately not follow this model?

Implaccable

Completely. This one is 3D printed and comes in a large palette of colors. I want to be honest about who I am, and I cannot afford shiny materials. I keep my feet on the ground, and I think this chain reflects that because it’s done with direct contact to my environment, in an approachable way.

Martin Sigler

Do you see having a bespoke chain as a way of reaffirming your independence?

Implaccable

Definitely. I don’t have a label per se. Actually, with my ‘TRACS’ chains, we built a network

that is called “Satellites Connectés” [Connected satellites]. In that network, there are beatmakers, photographers, stylists, etc., and the idea is that we connect and help each other whenever necessary. I only offer my chains to people I value and who are part of my team. I like the fact that it is attractive from the outside for its design and that to own one is to be a part of the family I’m building.

Nabihah Iqbal – Disintegration Record

Nabihah Iqbal is a London-based musician, DJ, and broadcaster, with a multidisciplinary background in ethnomusicology, history, and human rights law. In addition to releasing two albums, Iqbal has composed music for the Turner Prize, collaborated with the Barbican as part of its Basquiat retrospective, and sits on the board of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). Her chosen object is a first pressing of The Cure’s Disintegration, which she discovered by chance while touring her sophomore album Dreamer in Sicily.

Images: Arthur Comely

Words: Morna Fraser

Morna Fraser

What inspired you to choose The Cure’s Disintegration?

Nabihah Iqbal

Firstly, music is my favorite thing in the world. The Cure and this album are my favorites, too. Even though I had listened to a lot of The Cure’s music growing up, I only really dove into Disintegration more recently and I thought it was incredible. As a musician, and considering the kind of music I make, listening to that record feels aspirational—you just wish you could create something like that.

I picked that album specifically because I own a first pressing of it, which is quite a special version of the record. But at the same time, it’s not a super rare record—people can still find it and listen to it easily. When I stumbled upon this version in a record shop in Sicily—I was there for a gig—I was really excited to find it.

Morna Fraser

Are there any specific songs that really resonate with you?

Nabihah Iqbal

One track in particular – “The Same Deep Water as You” – really stands out for me. It wasn’t one of the big singles, so I only heard it when I listened to the full album for the first time. It completely stopped me in my tracks.

I think when Robert Smith made this album, he was going through a rough patch in his relationship. He’d been with his childhood sweetheart since they were teenagers, and I read somewhere that while making Disintegration, he thought he might lose her. They’re still together all these years later, but you can hear that emotional turmoil in the music. I think he has this gift of conveying so much emotion through the sound of his voice, regardless of the lyrics. It’s more about the sound and the delivery, which is then heightened by the instrumentation. That track is a perfect example of that. The whole album is deeply emotional. It evokes feelings of longing, frustration, deep love, and even happiness. It makes you want to convey that much emotion in your own work.

Morna Fraser

How would you say Disintegration has influenced the way you write? And when it comes to expressing emotion in your music, how do you decide what to keep personal and what to share?

Nabihah Iqbal

I think you can do both at the same time. Music is an outlet. For anyone creating—whether it’s music, art, or film—that’s their outlet. But that doesn’t mean it takes away control over how you present yourself in daily life. Perhaps it’s actually a luxury to have an artistic outlet, because most people don’t get that opportunity to express their emotions separately from their everyday interactions.

There’s definitely overlap in the sound of my music and The Cure’s. They’re one of my biggest influences in terms of songwriting, sonic palette, and pacing. What’s special about The Cure is that, despite being seen as an alternative or goth band, their songs are also great pop songs. People who don’t even know them will recognize “Friday I’m in Love”, “Lovesong”, or “Lullaby”. The songwriting and composition are that good.

Morna Fraser

As a multi-instrumentalist, with a breadth of knowledge of music and a background in Ethnomusicology, how much do you find yourself analysing the technicalities of a song, versus simply feeling it?

Nabihah Iqbal

There’s a bit of both. When you make music yourself, you appreciate great music even more because you understand how difficult it is to create just one song. You can put everything into it, but you never know how people will react. Will they identify with it? Will they want to hear it live? That’s completely out of your control.

When I released Dreamer, I didn’t know how it would be received, but after touring it around the world and seeing people connect with it, I felt like I had achieved what I set out to do.

When you listen to well-produced, well-written music, you appreciate it on another level. You start wondering about the recording process—what microphones they used, what compressors they applied to the drums, which studio it was recorded in, who the engineer was. You want to know everything.

Anysia Kim – Glass Ornament

Anysia Kym is a Bronx-raised producer, songwriter and musician. Last year, she released her first full-length solo project Truest. Across tracks like “Owed2Me” or “In Doubt”, which features frequent collaborator MIKE, her dreamy vocals coil around dense hip hop and drum and bass-inspired beats, invoking a hazy collage of sounds that reflect the city she’s from. In our conversation she presents a glass trinket holder in the shape of an outstretched palm that she inherited from her grandmother.

Images: Nuvany David

Words: Isabel Ling

Isabel Ling

Tell me a little bit about your object.

Anysia Kym

It's a keepsake from my grandmother's house. Honestly it's funny, because it's not something she made. I'm sure other Black households from the 90s have this piece, but it's one of the last things that I have from her apartment in the Bronx, so I've taken it with me to all my cribs. It can be used as a jewelry holder, for keys, probably as an ashtray too. I just keep it on my kitchen table now, it's very grounding.

Isabel Ling

What was your grandma like? I want to hear about growing up around her in the Bronx.

Anysia Kym

I grew up with my family in a neighborhood called Co-op City, and she lived there too. I lived in Section One, I can't remember the section she lived in. Co-op City is relatively small, it’s in the North Bronx and there are no trains over there, so it’s its own little community. My grandma was an artist. She went to The Fashion Institute of Technology. Her day job was as a banker. She was retired when I was a kid, so we would spend a lot of time together. She was a Sagittarius, she was strong and had a smart mouth, and she was a fighter. She was also the sweetest woman ever, and she spoiled the hell out of me. This object specifically just reminds me of the simple pleasantries of growing up in the Bronx. Co-Op City was a bunch of buildings connected by a park in the middle with a playground. We would go there and she would walk with her walker and I would be riding my bike around. So this object is very nostalgic to me, it reminds me of simpler times.

Isabel Ling

It’s nice that you can carry this piece of her with you. Was your grandma a homemaker?

Anysia Kym

Her home was filled with plants. She had a green thumb. I do not. She was also artistic, you could feel the use of her hands in every part of her apartment. And maybe that's why I'm so connected to this specifically. It's not a mold of her hand, but it’s so reminiscent of the woman that she was. For as long as I've known her, she was just always doing things with her hands—up until the very last moment of her life.

Isabel Ling

You’ve lived in Flatbush now for four years, how have you made a home for your-

self in your current space?

Anysia Kym

I’ve tried to make it cozy. My ideal home that I’m creating is a musical playground. I just want to wake up, roll out of bed, play my music, have my things around me. The way I make music is super tactile, so I need to have tangible equipment and instruments around me.

Isabel Ling

Do you have a specific memory growing up with music where you were like, ‘Ok, yeah, this is what I’m going to do.’?

Anysia Kym

I don't come from a musical family, but we played music in the home a lot. Like we had this big sound system. But also, I performed in talent shows when I was little.

Isabel Ling

Do you remember what you sang?

Anysia Kym

Girl, I was singing “1 Thing” by Amerie, which is not even my key in singing. But I loved performing, it was very uninhibited and playful. And that kind of helped me become the musician that I am today, because it’s always been about play for me. It’s about self discovery and self exploration. I didn’t come from a very technically advanced background in music, so I had to arrive here by myself.

Isabel Ling

I love your songwriting. I’m curious, are you ever writing for a character?

Anysia Kym

I treat songwriting the same way as I think a rapper would, I’m just telling a story. I think because most of my musician friends are rappers and because I grew up in the Bronx, hip hop is a huge part of how I put words together. But in terms of character, I’m definitely [writing] as a lover girl, I’m a yearner. The other day I tried to write a bad bitch song and it was so hard.

Isabel Ling

Well, I would argue that at the heart of it all bad bitches are lover girls.

Anysia Kym

Period! Exactly. But I have to stay true to myself, I love love.

Paola Buendia – ‘We Made Europe’ Sofa

“I want to make clothes that correspond to my different personalities,” says Paola Buendia, whose fittingly-titled label Personalities, was launched in 2022. Creating products such as graphic-emblazoned baby tees, oversized mohair shorts, and boxy, workwear-inspired jackets, while Buendia’s designs feel rooted in streetwear, it is not a typical streetwear brand. Personalities explores ideas around diasporic identity and community, in a way that evokes some of the genre’s prototypical innovators. Of both Spanish and Vili Congolese heritage, Buendia grew up in Paris, an environment steeped in both luxury fashion and the sartorial flamboyance of La Sape. Her creations, which sometimes seem incongruous on first viewing, skilfully merge research-based concepts and broad appeal. One example is a plastic tote bag, later refashioned into a sofa, which tells a story of European colonialism and the movement of different peoples.

Images: Antoine Carriou

Words: Martin Sigler

Martin Sigler

Your chosen object is a sofa that was part of the campaign for your 2023 collection ‘We Made Europe.’ What is the origin of this collection?

Paola Buendia

I designed the 'We Made Europe' collection after hearing the story of my uncle. He took

seven months to reach France from Congo through unconventional routes. This reality shook me, especially when I realized that the people who are now being rejected and abandoned in the Mediterranean Sea are the very ones who were welcomed with open arms when Europe needed a workforce to build itself. 'We Made Europe' is a tribute to them, and a reminder that today's Europe owes them.

Martin Sigler

Can you describe the collection?

Paola Buendia

The collection consists of a series of items, all of which feature a base sequence of black,

green, and red stripes, over which the stars from the European flag are applied, with one star replaced by the “P” of Personalities. People have associated the choice of colors and compositions with the Pan-African flag or the flag of Palestine. Although I am not against these associations, my initial idea was actually to use the colors found in the majority of the flags of the countries where the immigrants came from. So there are African countries, but also Asian

ones. Asian migration tends to be overlooked, and I also thought about that for this collection.

Martin Sigler

You also designed an accessory: the ‘Ghana Must Go’ bag, which draws on an essential item.

Paola Buendia

The ‘Ghana Must Go’ bag is a woven polyester carrier bag that the Ghanaians brought with them when they were deported from Nigeria in 1983 and which contained all their belongings. It is a bag that forms part of my references. I have seen it many times, and particularly during my trip to Senegal, where I saw it being used in many different ways: as a bag, as a cushion, and as a chair. As a functional item that embodies the idea of migration, it was essential to include one.

Martin Sigler

How did you end up with a sofa?

Paola Buendia

The sofa came quite naturally when I had to think about the collection photo shoot. We did it in a restaurant called Mao Grill in the third arrondissement of Paris. It was only afterwards that I understood the importance of this piece, with a little distance and having observed the reactions people had to it – particularly when I visited Japan and displayed the sofa there. It was a good way to connect. I also ended up organizing a giveaway and sent bags to anyone who could prove that they had made donations to organizations that were helping in ongoing conflicts. The video went viral and gave the sofa a whole new aura.

Martin Sigler

Beyond its colors and composition, the sofa conveys a feeling of stability, despite being made from unstable items. What do you think when you consider it now?

Paola Buendia

I realize more and more that it is a work of art. The way it is constructed is deliberately not smooth and perfect. I have received comments about the visible pallets, which apparently degrade the aesthetic. These kinds of comments are missing the point. I made the sofa with what I had to hand, and that is precisely the idea: to give a sense of my environment. My friend and close collaborator, Victorine Njiedjouk, helped me refine the sofa's design without pandering to an expected look. I have to admit that, after almost two years, this sofa resonates with a search for stability in my current life. A space where I can settle down and from which I can imagine new horizons.

Laurent Segretier – Autoportrait #1

For our video call, Laurent Segretier insisted on being in the presence of his work – a photograph of a sheathed BMW, titled Autoportrait #1. The artwork had recently been acquired by a friend and was hanging in his home. Segretier, who was born in Guadeloupe and splits his time between Paris and Hong Kong, is a photographer who predominantly works in fashion and music, collaborating regularly with the rapper Implaccable. Naturally, he is adept at altering perspectives. And here, as we spoke, I was treated to a striking mise en abîme, as Segretier spoke to me about this specific piece – a ‘self-portrait’ that loomed in the background.

Images: Laurent Segretier

Words: Martin Sigler

Martin Sigler

Your chosen object is a photograph, Autoportrait #1, depicting a veiled BMW, which was part of “Pump Fake,” an exhibition at Stems Gallery, Brussels, in 2018. In what context did you take this photo?

Laurent Segretier

I was working as a photographer in Asia, and one day, I found myself in a gathering of the ultra-rich. I was wandering around their garages, and this car intrigued me. At the time, my photos were looking at glitches, working with flashes, and bright colors. This time, I tried something else: I lowered the brightness and removed the flash. I came across this photo again a couple of years later and realized that it was me.

Martin Sigler

In what sense?

Laurent Segretier

Being a fashion photographer, I guess I was first attracted to the textile in which the car was covered. Also, the collector had to write 'BMW' to recognize it, but just by looking at the shape, I knew which model of car it was. When I was young, every five years or so, my father would travel to France from Guadeloupe to buy a BMW because it was cheaper. The model was always the 5 Series. We would go for rides with our cousins, enjoying the air conditioning that only a few cars had at that time. That car I photographed in the garage was a bit like a creature at rest, waiting to roar. It resonates with a mindset of being proactive but observant.

Martin Sigler

You are also holding the camera with which you took the photo: a Hasselblad 500 EL. What is your relationship to this object?

Laurent Segretier

Car enthusiasts often value the engine, speed, and how complex the mechanism of a certain car is. This can also be projected onto the camera. Just like that collector with his car, I have a multitude of cameras, but some are still waiting to be used. I like the way this camera sounds, the rattle, the weight; it’s all physics, which also gives a singular materiality to the photo. I had the photo printed on watercolor paper, I want to keep that matte effect, and the monochromatic grey-blue is also a nod to painter Pierre Soulages, whose work I value for the strength and texture of color and composition.

Ellis Gilbert – Wire Headphones

When asked to describe what he does for a living, 28 year old Ellis Gilbert says, “I’m a facilitator.” It’s a word that feels both true and inadequate for Gilbert, whose chief creative endeavour, Talk Nice, functions as something between a brand, creative agency, and youth program. When we speak, Gilbert has just released a collaboration with Nike the week prior, and the week before that he was pulling up to a school (along with Clint, of the London-based streetwear brand Corteiz) to give a talk to pupils. Other weeks, you might find him working with rapper AJ Tracey or on a script for a film. It makes sense that Gilbert is a connector; he exudes a warmth and humbleness that people naturally gravitate towards. “I've been very blessed to grow up in London, where I've met so many different amazing people,” he says. “Whether it’s people who work in shops, restaurants. People who do accounts or work as lawyers. We’ve just sort of built this beautiful community, where people exchange favors. Or now, we can actually pay each other for jobs… Talk Nice came to life because I realized that I had so many talented friends and family members, and sometimes they just needed a little push in the right direction.”

Images: Henry Goodfellow

Words: Calum Gordon

Calum Gordon

Your object of choice is some bog-standard wire headphones. Why?

Ellis Gilbert

I used to sneak into my sister's room when she was out. She had an iPod Nano, and I can remember hiding under her bed and listening to all her music. I think one of the first songs I listened to was by N.E.R.D, and I'd never heard anything like it. My dad is much more into rare groove, lover’s rock, soul music, and my mum listens to, like, Bob Dylan. I can remember sitting there and thinking, ‘What the hell is this?’ I'd never been to America – I think I'd maybe been on one holiday to Spain. It was like a portal to a different world. I still get that feeling sometimes when I listen to something from that era, or when I listen to a new piece of music that is really special. I have about 15 pairs of headphones in all my different bags – in my football bag, in my bag that I take on holiday with my passport. I'm always listening to something or communicating with someone. It’s a huge part of my life.

Calum Gordon

You were about 10 or 11 when you first heard that N.E.R.D song. What was life like for you then?

Ellis Gilbert

I was always traveling around by myself. Just jumping on the train and going to the other side of London – exploring, finding new stuff to eat, looking at shops. I was blessed to have that free-

dom from such a young age. I think having two big sisters – four and six years older – I was fascinated with what they were doing. They had such a big influence on me in terms of the music they were listening to and the clothes they were wearing.

Calum Gordon

We’ve spoken before about how you didn’t necessarily do the best at school. Was music also a form of escapism?

Ellis Gilbert

It was about getting away from what was going on in front of me. Traveling and being somewhere else. I've always had a crazy imagination, I would always be dreaming these big dreams… I went to a school that was very white and quite middle class, and there were a lot of kids listening to rock, and things like that. I didn't hate it, but it just wasn't me. It was after I got into college that I started being a bit more passionate about who I was. I started finding myself, and attracting people who were interested in the same things.

Calum Gordon

But you’ve always been curious.

Ellis Gilbert

I always found history fascinating. I got excluded from school, and history was one of the only subjects I found somewhat interesting. Even today, I woke up at 5am and then started watching something on the History Channel about Miles Davis. It’s nice how some things never really change. I guess it's important to just unapologetically be yourself.

Calum Gordon

Is that the message you try to instill in a lot of the people around you?

Ellis Gilbert

I do talks in schools quite often, and still do youth work. I always say, “Don't try to be anyone else other than who you are right now. Because that always leads to who you will be…” I did a talk last week in a school in Fulham, about 20 minutes from where I grew up. Clint [from Corteiz] came with me, and he pulled up in a Porsche GT3. The kids, seeing that, “he's from this area, he's a black guy that looks like me; he's got plats, and he’s wearing a tracksuit.” We’d just finished closing a huge deal that day, and being able to tell those kids that you can do that, just by being yourself. Some of them couldn't wrap their heads around it: “This is really what you can achieve from selling t-shirts?”

Calum Gordon

It also shows them that there’s more than one path to get to wherever it is they want to go.

Ellis Gilbert

I think being able to achieve cool stuff outside of the norm is brilliant. I believe that's one of the great powers of the internet. But it also applies so much pressure to people who are so much younger. I didn't think about making money until I was in a position where I had to. Whereas now there are kids as young as 12 coming to us and saying, “I'm interested in starting a dropshipping business. How could I potentially work with you?” I think, “Man, at 12 years old, you should still be running around the playground, grazing your knees.”

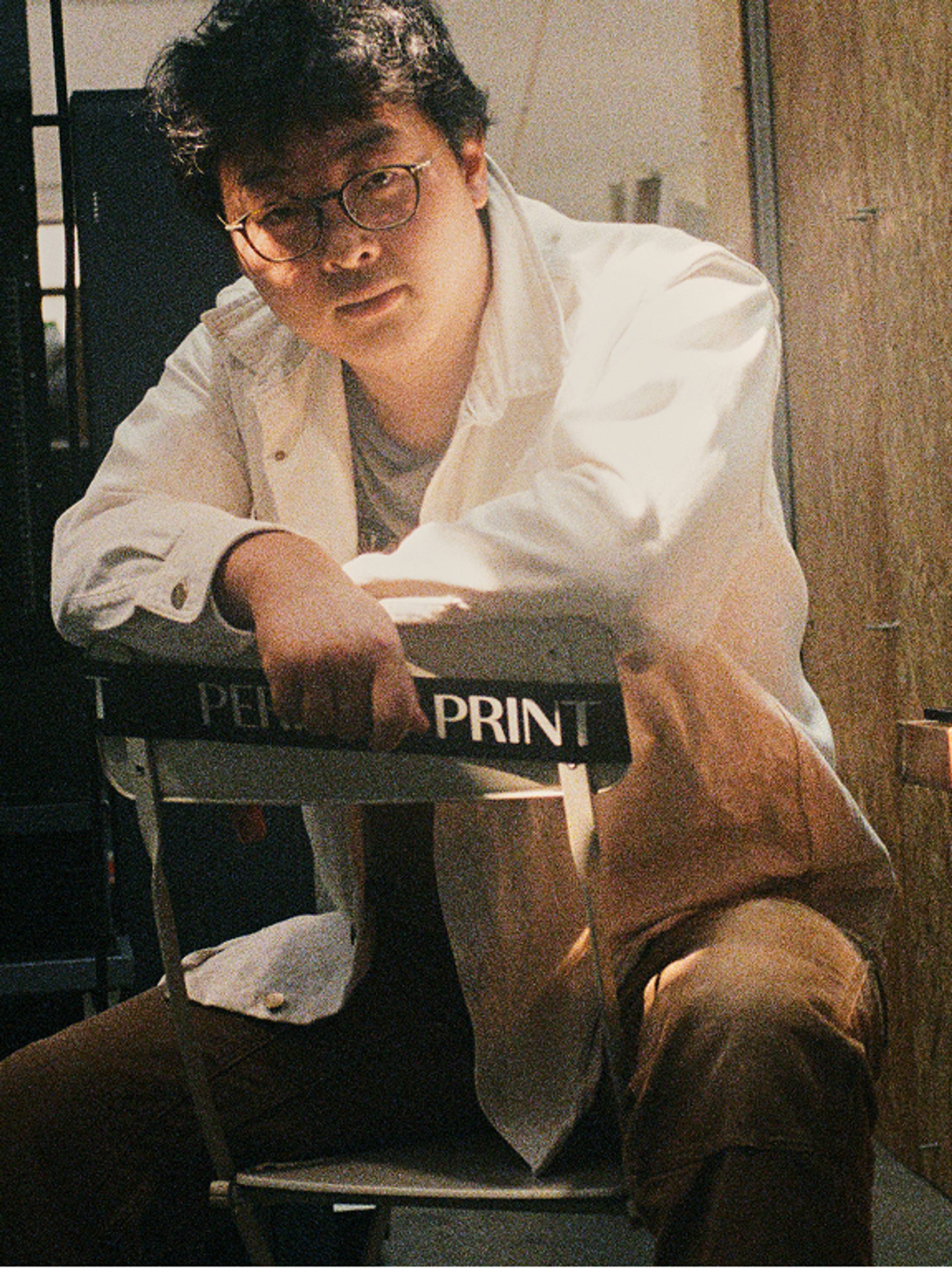

Wang Xin – Gaming Toy

Wang Xin is the founder of PERFECT PRINT, a Shanghai-based darkroom. Eschewing screens in favor of diving headfirst into trays of chemicals, they work with film, light, and time. A process that feels both raw and deliberate, their approach evokes a deeper, more personal investigation into the image as object and experience. “Between 2016 and 2018, we realized that color darkrooms had pretty much disappeared in China,” says Wang Xin. “That absence was the opportunity.” At PERFECT PRINT, people are invited to forge their own visual language; to leave their own trace. For this interview, Wang chose a lo-tech game console — a small, handmade object with simple mechanics and deep meaning. It’s a token of connection between friends, but also a mirror of the ethos behind PERFECT PRINT: hands-on, intimate. A little stubborn and entirely its own.

Images: Bilal Ali

Words: Didi Hu

Didi Hu

Tell us about the object you brought — the lo-tech game console made by PERFECT PRINT. What inspired you to create something like this, and to give it to your friends?

Wang Xin

When the studio first started, we were lucky to get a lot of support from friends. Things went surprisingly smooth in the beginning, and when our one-year anniversary came around, I wanted to make something fun as a little thank-you. Nothing too cliché or half-hearted. Around that time, I was pretty deep into lo-fi stuff, and the idea came to me: a tiny DIY game where you're just playing against yourself, like a bouncing ball you’re constantly trying to catch from both sides.

Didi Hu

What does this object mean to you?

Wang Xin

When you're obsessed with something that most people see as obsolete tech, it’s easy to get labeled as stubborn or nostalgic. But regardless of whether your tools are ‘outdated,’ doing something well still demands two things, real effort and belief. Neither is a given. You’ve got to wrestle with it and yourself. That’s what this game console reflects: that endless back-and-forth, a sparring match within. Once you've chosen a path, it’s only natural to start asking: What’s the point of it all? Am I chasing wins, or am I just caught in the rhythm of a ball that won’t stop bouncing? How do you even define victory? Maybe the only time we’ll know is when we catch a glimpse of ourselves through this little game — and whatever mindset we’re in at that moment holds the answer.

Didi Hu

Do you remember how you first got into film photography?

Wang Xin

I first came across Boris Mikhailov through Alec Soth’s work. Mikhailov’s images are beautiful, but the subject matter, which often depicts extreme poverty, can be dark. He helped me grapple with that eternal question when faced by the discomforting reality of the world we live in: ‘what is to be done?’ Sometimes there really isn’t a clear answer. Things happen, what can you do? Apart from documenting them, not much. But that act of recording becomes the response. Coming to terms with yourself isn’t about surrendering to the superego; it’s about picking up the tools you have and pushing forward. There’s courage in that.

Didi Hu

PERFECT PRINT has done a lot to open up access to analogue photography in Shanghai, from workshops to printing zines. Why is it important to you to foster personal connections?

Wang Xin

We’re simply responding to people’s curiosity. Today’s younger generation grew up entirely in the digital era. They didn’t inherit film photography through habit or nostalgia, so their curiosity is pure. That kind of curiosity is precious. Film is still a commodity after all, but what people get from using it – the meaning, the joy — that’s what reshapes habits, and builds new memories.

Didi Hu

You’ve said that PERFECT PRINT is about “finding a way to resist the digital void of a fast-food age.” What do you mean by that?

Wang Xin

Our core work happens within the world of fashion photography, which ironically helped fuel the

resurgence of film over the past decade. But fashion is also often dismissed as shallow or superficial. We’re not naïve enough to think we can resist consumerism all on our own, but what we can do is stay committed to the image. To not look up to it just because it’s glossy, and not look down on it just because it’s empty. We show respect for the work we touch every day. And I believe that kind of respect is contagious — it spreads, person to person, one frame at a time.

Nicholas Daley – ‘Reggae Klub’ T-Shirt

Nicholas Daley is a fashion designer from London who founded his eponymous label in 2015. He has since been shortlisted for the LVMH Prize, nominated for a British Fashion Award, and featured by the British Fashion Council and V&A Museum. Daley's chosen item is a ‘Reggae Klub’ t-shirt, printed in the late 70s, when his parents pioneered a reggae and dub night in Edinburgh.

Images: Arthur Comely

Words: Morna Fraser

Morna Fraser

Can you talk me through the origins of the t-shirt and why it is so special to you?

Nicholas Daley

It represents a DIY spirit—creating moments with your community through events and club spaces. It was about how people can be a part of that experience through merchandise, flyers, posters, and photographs. Luckily, my parents kept some of those memories from when they ran the club from 1978 to 1982. It’s a huge part of where I draw inspiration for my brand. My parents were the original torchbearers and I learned a lot from them. That’s why I always connect fashion with music and culture—they were the ones who introduced me to all of this. It’s been amazing to create designs and artworks that reflect my family’s influence on grassroots music in Britain.

There are only two t-shirts left from 1979, and I have one here in a box. It still has that real 70s feel. The cotton has worn in a unique way, and the artwork is flaking off, so it’s really lived in. There’s even paint on it, because my dad or my sister used it to paint our house once. It’s a t-shirt with its own story. When I do new versions of it at my brand, it never quite matches the original. But that’s part of what makes it special; how much history and life this t-shirt has seen.

Morna Fraser

Did you grow up with your parents sharing stories about the Reggae Klub, or did you discover it later through the memorabilia?

Nicholas Daley

I didn’t ask too many questions until I was about 16. I knew my parents had a club in Edinburgh, and they would talk about it to family and friends, but it wasn’t until later that I dug deeper. In part it was through my relationship with Nabihah, she started to point out how cool my parents were and how much they’d done. That made me realize their impact. Sometimes it takes someone else to shine a light on things.

It wasn’t until we went through some of the records and memorabilia that I fully understood. My dad even gave Nabihah a couple of records, which she now plays. It’s amazing to see how things get passed on and appreciated by others. We also did an exhibition in London, where Nabihah interviewed my parents about their experiences running the club. We’ve had friends in the music world create mixes and projects inspired by my parents’ work. It’s all about passing the torch and creating new links between the past and the present.

Morna Fraser

Your parents put a lot of effort into establishing the Reggae Klub and fostering a sense of community. How has their hard work and DIY spirit influenced your own perspective?

Nicholas Daley

Back then in Scotland, there weren’t many promoters playing reggae or Jamaican Caribbean sounds and West African highlife. So, my parents were on the forefront of that. They had people from all over the world coming to their events. For many, it felt like the closest thing to home at that time, whether you were black, brown, or from another background. The community was small, but my parents built a space where everyone felt welcome. They would even make food on the night – vegetable curries, rice and peas, and roti.

A lot was happening culturally at that time, like Rock Against Racism. My parents contributed in their own way. It was a pretty significant period with the rise of the far right, and what my parents did—promoting the opposite of what that rise stood for—was really important.

It’s similar to what’s happening in the world today. As a creative person, you have to ask yourself: what do you believe in? What community do you want to be surrounded by? What causes can you support through your work to inspire a different narrative? A lot of that is intertwined with how I work within my brand, even with the people I choose to work with—whether they’re from my generation or my parents’ generation. Cross-generational conversations are always important.

Morna Fraser

How did your parents design and produce the t-shirt?

Nicholas Daley

My dad made them in their apartment in Edinburgh. He got some blank t-shirts and used an iron-on process called flocking to create the lettering. Bob Marley was the number one artist, even back then, so my dad based the artwork on him. It’s similar to how gig merchandise started. Now, it's a massive industry, but back then, artists who didn’t have a lot of money would just make it at home.

On my mum’s side, she comes from a long tradition of hand knitting; my grandmother and great-grandmother worked in the jute mills in Dundee. So there was that DIY mentality. My mum and her friends knitted Rastafari jumpers, scarves, and woolly hats for people with dreadlocks. Everything was put together with whatever skills or crafts people had. It was all about using your resources. My parents did it for as long as they could until the economics just didn’t make sense anymore and they had to pause. They never thought it would be contextualized by me 30 years later. They just boxed it up and moved on with their lives, so I feel it’s my job to unbox it and bring it forward.